Continuing with Beverages these recipes involve adding fruit syrups to iced water and or soda water:

It is to be regretted that fruit syrups are not more extensively used in this country, as the addition of a few tablespoonfuls of a good fruit syrup to a glass of iced water, or soda water, produces a refreshing summer beverage that is far more desirable for general use than the majority of the liquids employed in this country. For the use of ladies and children, and all persons by whom intoxicating beverages are not used, they are strongly to be commended.

CURRANT SYRUP

—One pint of juice, two pounds of sugar. Mix together three pounds of currants, half white and half red, one pound of raspberries, and one pound of cherries, without the stones. Mash the fruit, and let it stand in a warm place for three or four days, keeping it covered with a coarse cloth or piece of paper with holes pricked in it to keep out any dust or dirt. Filter the juice, add the sugar in powder, finish in the water-bath, and skim it. When cold, put it into bottla, fill them, and cork well.

MORELLO CHERRY SYRUP

—Take the stones out of the cherria, mash them, and press out the juice in an earthen pan. Let it stand in a cool place for two days, then filter; add two pounds of sugar to one pint of juice, finish in the water-bath, or stir it well on the fire, and give it one or two boils.

MULBERRY SYRUP

—One pint of juice, one pound twelve ounces of sugar. Press out the juice, and finish as cherry syrup.

Gooseberry Syrup.—One pint of juice, one pound twelve ounces of sugar. To twelve pounds of ripe gooseberries add two pounds of cherries without stones, squeeze out the juice, and finish as others.

LEMON SYRUP

—One pint and a quarter of juice, two pounds of sugar. Let the juice stand in a place to settle. When a thin skin is formed on the top pour it off and filter; add the sugar, and finish in the water-bath. If the flavor of the peel is preferred with it, grate off the yellow rind of the lemons and mix it with the juice to infuse, or rub it off on part of the sugar, and add it with the remainder when you finish it.

RASPBERRY VINEGAR SYRUP

—One pint of juice, two pints of vinegar, four pounds and a half of sugar. Prepare the juice as before, adding the vinegar with it. Strain the juice and boil to the pearl. A very superior raspberry vinegar is made by taking three pounds of raspberries, two pints of vinegar, and three pounds of sugar. Put the raspberries into the vinegar without mashing them, cover the pan close, and let it remain in a cellar for seven or eight days; then filter the infusion, add the sugar in powder, and finish in the water-bath. This is superior to the first, as the beautiful aroma of the fruit is not lost in the boiling.

SOUR ORANGE SYRUP

—Peel the oranges carefully, then squeeze the juice and strain it, so as to extract the seed and white fibrous substances, which are very bitter. Add one pound of loaf sugar to one pint of juice, and boil it in a preserving kettle. Stir frequently, and skim well. Boil until it is a rich syrup. When nearly cold, bottle, cork, and seal.

Syrup of Cloves

—Put a quarter of a pound a of cloves to a quart of boiling water, cover close, set it over a fire, and boil gently half an hour; then drain and add to a pint of the liquor two pounds of loaf sugar, clear it with the whites of two eggs, beaten up with cold water, and let it simmer till it is strong syrup. Preserve it in phials, close corked.

ORANGE SYRUP

-Select ripe and thin-skinned fruit. Squeeze the juice through a sieve, and to every pint add one pound and a half of loaf sugar. Boil it slowly, and skim as long as the scum rises; then take it off, let it grow cold, and bottle it. Two tablespoonfuls of this syrup mixed with melted butter make a nice sauce for plum or batter puddings. Three tablespoonfuls of it in a glass of ice water make a delicious beverage.

Source: The Godey's Lady's Book Receipts ©1870

The 19th century was full of innovation, exploration and is one of the most popular eras for writing historical fiction. This blog is dedicated to tiny tidbits of information that will help make your novel seem more real to the time period.

Monday, June 30, 2014

Friday, June 27, 2014

Baths & Bathing

Hi all,

I thought this a rather interesting tidbit regarding baths and bathing taken from "A Cyclopaedia of Six Thousand Practical Receipts" ©1851

BATHS, BATHING. General Remarks. The practice of bathing is not only an act of cleanliness, but is eminently conducive to health. The delicate pores of the skin soon become choked by the solid matter of the perspiration and the accumulation of dirt, and require frequent ablution with water, to preserve their natural functions in a state of activity. The mere wearing of flannel and washing the more exposed parts of the body, and the daily use of clean linen, is but an imperfect attempt at cleanliness, without being accompanied by entire submersion of the body in water. The phlegmatic Englishman, unlike his liveiy French neighbor, seems perfectly incredulous on this point, and would sooner spend his sixpence or his shilling in a glass of grog, or a ride to Greenwich, than in the healthy recreation of the bath.

Bathing is not only conducive to cleanliness, but to both the physical and mental health. The body cannot be in a state of lively health, while the proper offices of the skin are interfered with, any more than would be the case with either of the other excretory organs, placed in a like condi tion. Nor can the mind, dependent as it is on the organization of the body, escape unharmed, when the animal functions are imperfectly performed. Intellectual and moral vigor are universally promoted by the imperceptible yet controlling influence of the physical system, and he who would increase the former, cannot go on a safer method than that which tends to preserve or improve the health.

"On the continent, 'Maisons des Bains' or bathing-houses, are almost as numerous as the chemists and druggists are in this country. The inferenco necessarily is, that bathing in France is as much patronized as physic is in England. The French need the latter less, because they live more temperately, are less ground down to think and work; and because they pertorm general personal ablution (to the benefit of one of the mos* important functions of life, namely, free perspiration) with as much zeal as though it were a religious duty. The inducement to such frequent use of the warm bath among our neighbors, may be fancied to be the low charges for bathing, and the little value the Messieurs attach to their own time. The first notion is a fallacy. Warm bathing on the continent is not cheaper in comparison with all the other necessaries or luxuries of life, viewed in connection with a foreigner's resources, than it is in England. With regard to the apparently little importance they attach to their own time, they are wise enough to discover, that life is not one jot sweeter by passing sixteen hours a day behind the desk or counter, to the exclusion of all recreation, except recreation be to count the gains of such exilement; or to indulge the hope of amassing a sufficiency to do the ' important' at the close of a wearied life, when and which the infirmities of age forbid to enjoy. A Frenchman lives, works, and enjoys himself to the last. Prince Talleyrand died in armor; his life was a bouquet in which all but the sweetest flowers were excluded. A Frenchman takes the bath for the mental and bodily gratification it affords; he can appreciate the luxury of it, while at the same time he is sensible of its healthfulness. An Englishman is such a stiffnecked fellow, that in most things, he will only do that which pleases him best, and his standard of pleasure is estimated by that which adds most to his hoard, and which gives the greatest amount of satisfaction to the inward man. Advise him to take a warm bath; the answer is, he cannot spare the time, and he hates the bother of uncravating, &c. The waste of the one and the trouble of the other add not to his income, whatever they may to his health. The roast beef, the brandied wines, and the London-brewed are his stomach's deities, the minor godships being blue pills and black draughts. The latter are indispensable attendants upon the former, to temper down Mr. Bull, lest he become a giant in noses and carbuncles. A Frenchman knows no ill but what pleasure denies; he rarely has dyspepsia, gout, rheumatism, or fevers. Half his life is spent in Elysium,—half ours in Purgatory. Indigestion, headaches, restless nights—the blues when awake, and the terribles when asleep—fall to the lot of the mind-absorbed and grossly-fed Londoner, while our lively Parisian, with his light meal and still more lightsome body, finds trouble only in broken limbs, or positive starvation."

The warm bath, especially, is one of the most valuable, but most neglected remedies which we possess. It is generally imagined by Englishmen, that bathing is but little fitted for their country, owing to the changefulness of the climate, and that to attempt to place a sick man in a bath in any other than the mildest weather, would be to subject him to all the horrors of " sniffling, sneezing, coughing, and relapse." But that such results of bathing have no existence beyond the minds of the fearful, ignorant, and prejudiced, must be acknowledged by every candid person. Even the cold bath, as in the treatment termed "hydropathy," is beneficial when applied with judgment; and it is only when common discretion is not exercised, that bathing under any shape ever proves injurious.

Some persons are very susceptible of taking cold, and are themselves "living barometers;"

but even to them warm bathing would prove ad. vantageous. One half of the rheumatic twinges, swollen limbs, and cramped joints that occur in such persons, would give way before proper perseverance and confidence in this remedy.

Whenever in delicate persons the cold bath is deemed proper, the warm, tepid, and cool bath may be used as a preparative, and when the former is at length adopted, it should be at first only for one or two minutes at a time, gradually increased to a quarter of an hour or twenty minutes; care being taken never to remain immersed sufficiently long to induce a sensation of cold on coming out. A healthy reaction should follow the bath, and a pleasing glow of warmth should diffuse itself over the surface of the body. If this be not the case, the bath has either been indulged in too long, or been injudiciously taken. When any symptoms appear that contra-indicate the use of the cold bath, the tepid, warm, or vapor bath may be substituted, according to circumstances.

In conclusion, I may remark, that bathing, especially in water at a temperature nearly similar to that of our bodies, (tepid bath,) is at once lie of the most cleanly and health-preserving luxuries, or, I should say, necessaries of life. The following short notice of each description of bath, is all the space that can be spared for this subject.

I thought this a rather interesting tidbit regarding baths and bathing taken from "A Cyclopaedia of Six Thousand Practical Receipts" ©1851

BATHS, BATHING. General Remarks. The practice of bathing is not only an act of cleanliness, but is eminently conducive to health. The delicate pores of the skin soon become choked by the solid matter of the perspiration and the accumulation of dirt, and require frequent ablution with water, to preserve their natural functions in a state of activity. The mere wearing of flannel and washing the more exposed parts of the body, and the daily use of clean linen, is but an imperfect attempt at cleanliness, without being accompanied by entire submersion of the body in water. The phlegmatic Englishman, unlike his liveiy French neighbor, seems perfectly incredulous on this point, and would sooner spend his sixpence or his shilling in a glass of grog, or a ride to Greenwich, than in the healthy recreation of the bath.

Bathing is not only conducive to cleanliness, but to both the physical and mental health. The body cannot be in a state of lively health, while the proper offices of the skin are interfered with, any more than would be the case with either of the other excretory organs, placed in a like condi tion. Nor can the mind, dependent as it is on the organization of the body, escape unharmed, when the animal functions are imperfectly performed. Intellectual and moral vigor are universally promoted by the imperceptible yet controlling influence of the physical system, and he who would increase the former, cannot go on a safer method than that which tends to preserve or improve the health.

"On the continent, 'Maisons des Bains' or bathing-houses, are almost as numerous as the chemists and druggists are in this country. The inferenco necessarily is, that bathing in France is as much patronized as physic is in England. The French need the latter less, because they live more temperately, are less ground down to think and work; and because they pertorm general personal ablution (to the benefit of one of the mos* important functions of life, namely, free perspiration) with as much zeal as though it were a religious duty. The inducement to such frequent use of the warm bath among our neighbors, may be fancied to be the low charges for bathing, and the little value the Messieurs attach to their own time. The first notion is a fallacy. Warm bathing on the continent is not cheaper in comparison with all the other necessaries or luxuries of life, viewed in connection with a foreigner's resources, than it is in England. With regard to the apparently little importance they attach to their own time, they are wise enough to discover, that life is not one jot sweeter by passing sixteen hours a day behind the desk or counter, to the exclusion of all recreation, except recreation be to count the gains of such exilement; or to indulge the hope of amassing a sufficiency to do the ' important' at the close of a wearied life, when and which the infirmities of age forbid to enjoy. A Frenchman lives, works, and enjoys himself to the last. Prince Talleyrand died in armor; his life was a bouquet in which all but the sweetest flowers were excluded. A Frenchman takes the bath for the mental and bodily gratification it affords; he can appreciate the luxury of it, while at the same time he is sensible of its healthfulness. An Englishman is such a stiffnecked fellow, that in most things, he will only do that which pleases him best, and his standard of pleasure is estimated by that which adds most to his hoard, and which gives the greatest amount of satisfaction to the inward man. Advise him to take a warm bath; the answer is, he cannot spare the time, and he hates the bother of uncravating, &c. The waste of the one and the trouble of the other add not to his income, whatever they may to his health. The roast beef, the brandied wines, and the London-brewed are his stomach's deities, the minor godships being blue pills and black draughts. The latter are indispensable attendants upon the former, to temper down Mr. Bull, lest he become a giant in noses and carbuncles. A Frenchman knows no ill but what pleasure denies; he rarely has dyspepsia, gout, rheumatism, or fevers. Half his life is spent in Elysium,—half ours in Purgatory. Indigestion, headaches, restless nights—the blues when awake, and the terribles when asleep—fall to the lot of the mind-absorbed and grossly-fed Londoner, while our lively Parisian, with his light meal and still more lightsome body, finds trouble only in broken limbs, or positive starvation."

The warm bath, especially, is one of the most valuable, but most neglected remedies which we possess. It is generally imagined by Englishmen, that bathing is but little fitted for their country, owing to the changefulness of the climate, and that to attempt to place a sick man in a bath in any other than the mildest weather, would be to subject him to all the horrors of " sniffling, sneezing, coughing, and relapse." But that such results of bathing have no existence beyond the minds of the fearful, ignorant, and prejudiced, must be acknowledged by every candid person. Even the cold bath, as in the treatment termed "hydropathy," is beneficial when applied with judgment; and it is only when common discretion is not exercised, that bathing under any shape ever proves injurious.

Some persons are very susceptible of taking cold, and are themselves "living barometers;"

but even to them warm bathing would prove ad. vantageous. One half of the rheumatic twinges, swollen limbs, and cramped joints that occur in such persons, would give way before proper perseverance and confidence in this remedy.

Whenever in delicate persons the cold bath is deemed proper, the warm, tepid, and cool bath may be used as a preparative, and when the former is at length adopted, it should be at first only for one or two minutes at a time, gradually increased to a quarter of an hour or twenty minutes; care being taken never to remain immersed sufficiently long to induce a sensation of cold on coming out. A healthy reaction should follow the bath, and a pleasing glow of warmth should diffuse itself over the surface of the body. If this be not the case, the bath has either been indulged in too long, or been injudiciously taken. When any symptoms appear that contra-indicate the use of the cold bath, the tepid, warm, or vapor bath may be substituted, according to circumstances.

In conclusion, I may remark, that bathing, especially in water at a temperature nearly similar to that of our bodies, (tepid bath,) is at once lie of the most cleanly and health-preserving luxuries, or, I should say, necessaries of life. The following short notice of each description of bath, is all the space that can be spared for this subject.

Thursday, June 26, 2014

Odds & Ends for the 1871 Housewife

Miss Beecher has a informative list of Odd's and Ends for the housewife to take care of her idle time. Perhaps, some of the items on this list will give your character a jolt in what is or is not there.

There are certain odds and ends, where every house tipper will gain much by having a regular time to attend to them. Let this time be the last Saturday forenoon in every month, or any other time more agreeable, but let there be a regular fixed time once a month, in which the housekeeper will attend to the following things:

First, go around to every room, drawer, and closet in the house, and see what is out of order, and what needs to be done, and make arrangements as to time and manner of doing it.

Second, examine the store-closet, and see if there is a proper supply of all articles needed there.

Third, go to the cellar, and see if the salted provision, vegetables, pickles, vinegar, and all other articles stored in the cellar are in proper order, and examine all the preserves and jellies.

Fourth, examine the trunk, or closet of family linen, and see what needs to be repaired and renewed.

Fifth, see if there is a supply of dish towels, dish cloths, bags, holders, floor cloths, dust cloths, wrapping paper, twine, lamp-wicks, and all other articles needed m kitchen work.

Sixth, count over the spoons, knives, and forks, and examine all the various household utensils, to see what need replacing, and what should be repaired.

A housekeeper who will have a regular time for attending to these particulars, will find her whole family machinery moving easily and well; but one who does not, will constantly be finding something out of joint, and an unquiet, secret apprehension of duties left undone, or forgotten, which no other method will so effectually remove.

A housekeeper will often be much annoyed by the xccumulation of articles not immediately needed, that must be sared for future use. The following method, adopted by a thrifty housekeeper, may be imitated with advantage. She bought some cheap calico, and made bags of various sizes, and wrote the following label' with indelible ink on a bit of broad tape, and sewed them on one side of the bags:—Old Linens; Old Cottons; Old Black Silks; Old Colored Silks j Old Stockings; Old Colored Woollens; Old Flannels; New Linen; New Cotton; New Woollens; New Silks; Pieces of Dresses; Pieces of Boys' Clothes, &c. These bags were hung around a closet, and filled with the above articles, and then it was known where to look for each, and where to put each when not in use.

Another excellent plan is for a housekeeper once a month to make out a bill of fare for the four weeks tc come. To do this, let her look over this book, and find out what kind of dishes the season of the year and her own stores will enable her to provide, and then make out a list of the dishes she will provide through the month, so as to have an agreeable variety for breakfasts, dinners, and suppers. Some systematic arrangement of this kind at regular periods will secure great comfort and enjoyment to a family.

Source: Miss Beecher's Domestic Receipt Book ©1871

There are certain odds and ends, where every house tipper will gain much by having a regular time to attend to them. Let this time be the last Saturday forenoon in every month, or any other time more agreeable, but let there be a regular fixed time once a month, in which the housekeeper will attend to the following things:

First, go around to every room, drawer, and closet in the house, and see what is out of order, and what needs to be done, and make arrangements as to time and manner of doing it.

Second, examine the store-closet, and see if there is a proper supply of all articles needed there.

Third, go to the cellar, and see if the salted provision, vegetables, pickles, vinegar, and all other articles stored in the cellar are in proper order, and examine all the preserves and jellies.

Fourth, examine the trunk, or closet of family linen, and see what needs to be repaired and renewed.

Fifth, see if there is a supply of dish towels, dish cloths, bags, holders, floor cloths, dust cloths, wrapping paper, twine, lamp-wicks, and all other articles needed m kitchen work.

Sixth, count over the spoons, knives, and forks, and examine all the various household utensils, to see what need replacing, and what should be repaired.

A housekeeper who will have a regular time for attending to these particulars, will find her whole family machinery moving easily and well; but one who does not, will constantly be finding something out of joint, and an unquiet, secret apprehension of duties left undone, or forgotten, which no other method will so effectually remove.

A housekeeper will often be much annoyed by the xccumulation of articles not immediately needed, that must be sared for future use. The following method, adopted by a thrifty housekeeper, may be imitated with advantage. She bought some cheap calico, and made bags of various sizes, and wrote the following label' with indelible ink on a bit of broad tape, and sewed them on one side of the bags:—Old Linens; Old Cottons; Old Black Silks; Old Colored Silks j Old Stockings; Old Colored Woollens; Old Flannels; New Linen; New Cotton; New Woollens; New Silks; Pieces of Dresses; Pieces of Boys' Clothes, &c. These bags were hung around a closet, and filled with the above articles, and then it was known where to look for each, and where to put each when not in use.

Another excellent plan is for a housekeeper once a month to make out a bill of fare for the four weeks tc come. To do this, let her look over this book, and find out what kind of dishes the season of the year and her own stores will enable her to provide, and then make out a list of the dishes she will provide through the month, so as to have an agreeable variety for breakfasts, dinners, and suppers. Some systematic arrangement of this kind at regular periods will secure great comfort and enjoyment to a family.

Source: Miss Beecher's Domestic Receipt Book ©1871

Wednesday, June 25, 2014

Tuesday, June 24, 2014

Advertising and Selling Tea

This tidbit is really about the art of advertising during the 19th century. However, the example is from a small book "Tea-Blending as a Fine Art"©1896 and has a chapter dedicated to how to advertise and sell tea. Below is a large excerpt from this book.

ART OF ADVERTISING TEAS.

(1.) Make an attractive display of your Teas, utilizing a show-case when convenient to do so for an exhibit of your finest varieties, having on such kind a neatly printed show-card after the following styles:—

"We sell Tea to sell again." "If it's anything in Tea, we've got it." "What you require in Tea is to be had here." "It's our pleasure to please you in Tea." "A good Tea for you is a gain for us." "Our Teas make our prices look small." "Every Tea as advertised, or—a little better." "No Tea customer must leave our store dissatisfied."

"You can make a little money go far by buying your Teas here."

"Misrepresentation in our Teas would be the suicide of our business."

"Our Teas are pure, pungent, piquant, perfect."

"Blank's Teas are distinctive in leaf, distinctive in liquor, distinctive in flavor."

"Blank's Teas are cleanest in leaf, heaviest in body, richest in flavor."

It is an old axiom "that goods well bought are half sold," and the same is equally true of Teas well displayed in the dealer's store or window.

Goods conveniently placed and marked save time, temper, labor and money in showing. When a line of Teas have been placed in a prominent position, with the prices plainly marked and attached to them, they often become their own salesmen.

A good customer secured being a promise of larger salary in the future, the good Tea salesman will always increase your business in addition to adding to your profits, while the poor Tea salesman will only serve to drive away customers and may ruin your Tea trade in other respects.

In a grocer's window Tea should always be given a prominent position, especially if neatly sealed up in handsome packages, or even "dummies" may be conveniently used for the purpose with good effect. But they should be perfectly fresh and clean, in fact, every package exhibited should be carefully examined and made as inviting as possible. It is not prudent, however, to make too copious a display of loose Teas as it collects dust and absorbs moisture in addition to the loss resulting from deterioration in strength and flavor, its appearance also disgusting the customers who are apt to reflect that they must become the consumers of the article when removed from the window. Again, nothing can look worse than a window in Summer sprinkled over with flies—dead and alive—or in Winter than a heap of damp and discolored Teas, so that all loose Teas should invariably be scrupulously covered over with well-polished glass-shades or invitingly displayed in small sample bowls appropriately labeled. The colors also should harmonize in order that the window will look well, attract customers' attention and gain favorable criticism. Care should also be taken that the Teas be not kept too near the heat of gas, heat or sun, or exposed to these influences as they are often irretrievably ruined thereby.

There is great art in dressing a window well with Teas; some dealers having a natural talent for it, while others can only imitate it indifferently, others, again, being entirely incapable of either. The art, however, has a very important bearing in the sale of Teas and is certainly worth careful study on the part of the dealer, as a well-dressed and judicious arrangement of Teas in a window is sure to attract attention and admiration from the passers-by, people turning again to look at and admire it. So that a Tea window-dresser should possess good natural taste as well as be a good designer and systematic arranger of the goods. All labels and show-cards should always be neat, clean and bright, that is, removed often, and when prices are affixed they should be reasonable, neither too high nor too low, as the best customers like moderation, but Teas that are exceptionally cheap and plentiful should always be marked in plain figures.

Cleanliness goes a long way in selling Teas, as in all things people want to eat and drink, and a clean store is a customer's delight, so that dusting and sweeping are among the mast important functions of a well-kept Tea store. These duties should be performed every day, or oftener, and should be done under the best conditions possible, as all dust is destructive to Tea, and all losses thus entailed must be kept down as far as possible.

Do not attempt to place too many varieties or grades in the window at the same time, as such a display serves only to confuse the mind and weary the eyes of spectators, neither aim at quantity. A good plan for the dealer is first to consider what Teas are most in demand or most likely to be in request in his neighborhood and not simply what he has most of. Then making out a list of what he decides to show he should map out in his mind the best manner of arranging the same.

The window display should be frequently altered and the Teas never allowed to remain until they become discolored, stale and dirty, as in such cases instead of attracting trade it will only serve to repel it, and no favorite cats should be allowed to sun themselves near the Tea no matter how sleek or handsome they may be. In emptying the window also each package should be carefully examined, cleaned and replaced in stock, ready for sale and hidden out of sight regardless of its condition. Carelessness in this matter is a source of serious loss.

The Tea salesman of the future must not be illiterate or ignorant of his business; the day for such has gone by in this country, never to return. Any salesman can take orders but very few can impart information about the Teas he sells or tries to sell, so that the customer learns nothing from contact with him, while many of the best purchasers like to talk to an intelligent and well-posted man in order to learn all they can about the article. Again, it is the Tea salesman who knows the meaning and feels the power of what he is talking about that will naturally speak earnestly and with the right emphasis; while otherwise he will not emphasize it at all and very often a good sale of Tea depends on the proper emphasis given to a few important words in reply to the customer's question about the article. The good Tea salesman should speak to explain, convince and persuade and should keep this final object constantly in mind; he should know instantly the effect he is producing on the customer, and the more favorable the effect is the better he can talk, because his faculties are thus encouraged. But when a question can be made clear at all it is made all the clearer by brevity, as all sensible intending purchasers prefer evidence to eloquence.

Many Tea dealers and employees have an idea that a certain kind of smartness in dealing is a praiseworthy business qualification, and that success in the Tea business depends largely on that kind of sharpness and chicanery in dealing with their Tea customers. This is a most mistaken idea, if not worse, as it should be the first and fundamental effort on the part of every business man to gain the respect and confidence of his patrons, not their ill-will and contempt by getting the best of them, as he foolishly supposes. As a customer who once finds himself deceived in either quality or price in buying Teas will consequently be suspicious ever afterward of the dealer who has deceived him, so that the dealer who thought himself so sharp in making a little extra money on the first transaction loses in the end a good and prompt-paying customer who might have traded with him for years if he had but retained his good opinion and induced him by fair dealing to continue his patronage. It has been wisely and sensibly said by President Lincoln that "You may fool some of the people all the time, and all the people some of the time, but you cannot fool all the people all the time." Enduring prosperity in the Tea business cannot be founded on cunning and deception, as the tricky and deceitful Tea dealer is sure to fall a victim sooner or later to the influences which are forever working against him. His business structure is built in sand and its foundations will be certain to give way and crush him in the end. Young men in the line particularly cannot give these truths too much weight and importance, as the future of the young Tea dealer is secure who repudiates every form of deception and double dealing, thereby laying the foundation of his business career on the enduring principles of ever-lasting truth and honest dealing.

A reputation for intelligence and truthfulness is indispensable to a permanent and satisfying success in the Tea business, and politeness is also among the few weapons that the small Tea dealer has at his command to meet the competition of larger dealers who

buy their Teas more cheaply. But the larger the business the greater the number of hands required and consequently the less chance of the customers being treated with deference. That these advantages are not fully realized and utilized by the average retailer is well known to all who come in contact with them. One important point in particular to be impressed upon your assistants is the necessity of careful and polite attention to the smallest customers. There is an old and trite adage which says, "When you buy, keep one eye on the goods and the other on the seller, but when you sell, keep both eyes on the buyer." Customers are drawn to the dealer who greets them cordially, treats them with civility, shows them little courtesies, manifests an interest in their wants and seeks to gain their confidence. Do not imagine that customers consider cheap Teas and "cut prices" are the equivalent for such treatment, for if you do you will soon have to discontinue business for lack of brains or be sold out altogether, although you may charge your misfortune to other causes.

Don't.

Don't smoke in your store or encourage your customers to do so.

Don't let your store smell of mice and rats, or allow dogs or cats around the store.

Don't permit your store to smell of oil, fish, soap, strong cheese or other loud smelling articles.

Don't clean your scales, weights and other utensils or wash your counters and shelves in the presence of customers.

Don't spit on your store floor or allow others to do so, and never be without a clean handkerchief, even when you wear an apron.

Don't use the same set of scales, weights or scoops for sugar, flour, rice, cheese or other articles for Tea, as they invariably impart their odor to it.

Don't store your Teas in damp places or they will soon contract a musty, mildewy smell and flavor, and be careful of wet cellars, which produce the same results.

Don't permit your store to become a lounging place for idlers, local gossipers or cheap politicians, no matter how profitable they may appear to you, as particular customers do not like to have their business exposed to such hangers-on.

Don't have dirty hands, face or wear your fingernails in half-mourning, and don't wear a sour, illtempered face—nothing so repels a sensitive customer —but cultivate a cheerful countenance at all times and under all circumstances. In other words, if you do not possess this virtue at least assume it.

Don't overbuy, as most Teas deteriorate by long keeping, particularly after opening, get dirty, lose strength and therefore become unsalable. And when you happen to get stuck on a bad lot dispose of them quickly and as privately as you can, even at a sacrifice. Above all things don't try to work them off on your customers, either regular or casual, as nothing will ruin your Tea trade quicker or surer.

In conclusion, be thorough in all you undertake, as nothing conduces like thoroughness and sincere earnestness to build up and retain a successful Tea business. And remember that it is much easier to do particular work yourself than to show others how to. Master the whole business and the road to success has been mapped out, as most certainly the dealer who notes what a community is most in need of and supplies that want most thoroughly possesses the attributes of a successful Tea merchant.

ART OF ADVERTISING TEAS.

(1.) Make an attractive display of your Teas, utilizing a show-case when convenient to do so for an exhibit of your finest varieties, having on such kind a neatly printed show-card after the following styles:—

"We sell Tea to sell again." "If it's anything in Tea, we've got it." "What you require in Tea is to be had here." "It's our pleasure to please you in Tea." "A good Tea for you is a gain for us." "Our Teas make our prices look small." "Every Tea as advertised, or—a little better." "No Tea customer must leave our store dissatisfied."

"You can make a little money go far by buying your Teas here."

"Misrepresentation in our Teas would be the suicide of our business."

"Our Teas are pure, pungent, piquant, perfect."

"Blank's Teas are distinctive in leaf, distinctive in liquor, distinctive in flavor."

"Blank's Teas are cleanest in leaf, heaviest in body, richest in flavor."

It is an old axiom "that goods well bought are half sold," and the same is equally true of Teas well displayed in the dealer's store or window.

Goods conveniently placed and marked save time, temper, labor and money in showing. When a line of Teas have been placed in a prominent position, with the prices plainly marked and attached to them, they often become their own salesmen.

A good customer secured being a promise of larger salary in the future, the good Tea salesman will always increase your business in addition to adding to your profits, while the poor Tea salesman will only serve to drive away customers and may ruin your Tea trade in other respects.

In a grocer's window Tea should always be given a prominent position, especially if neatly sealed up in handsome packages, or even "dummies" may be conveniently used for the purpose with good effect. But they should be perfectly fresh and clean, in fact, every package exhibited should be carefully examined and made as inviting as possible. It is not prudent, however, to make too copious a display of loose Teas as it collects dust and absorbs moisture in addition to the loss resulting from deterioration in strength and flavor, its appearance also disgusting the customers who are apt to reflect that they must become the consumers of the article when removed from the window. Again, nothing can look worse than a window in Summer sprinkled over with flies—dead and alive—or in Winter than a heap of damp and discolored Teas, so that all loose Teas should invariably be scrupulously covered over with well-polished glass-shades or invitingly displayed in small sample bowls appropriately labeled. The colors also should harmonize in order that the window will look well, attract customers' attention and gain favorable criticism. Care should also be taken that the Teas be not kept too near the heat of gas, heat or sun, or exposed to these influences as they are often irretrievably ruined thereby.

There is great art in dressing a window well with Teas; some dealers having a natural talent for it, while others can only imitate it indifferently, others, again, being entirely incapable of either. The art, however, has a very important bearing in the sale of Teas and is certainly worth careful study on the part of the dealer, as a well-dressed and judicious arrangement of Teas in a window is sure to attract attention and admiration from the passers-by, people turning again to look at and admire it. So that a Tea window-dresser should possess good natural taste as well as be a good designer and systematic arranger of the goods. All labels and show-cards should always be neat, clean and bright, that is, removed often, and when prices are affixed they should be reasonable, neither too high nor too low, as the best customers like moderation, but Teas that are exceptionally cheap and plentiful should always be marked in plain figures.

Cleanliness goes a long way in selling Teas, as in all things people want to eat and drink, and a clean store is a customer's delight, so that dusting and sweeping are among the mast important functions of a well-kept Tea store. These duties should be performed every day, or oftener, and should be done under the best conditions possible, as all dust is destructive to Tea, and all losses thus entailed must be kept down as far as possible.

Do not attempt to place too many varieties or grades in the window at the same time, as such a display serves only to confuse the mind and weary the eyes of spectators, neither aim at quantity. A good plan for the dealer is first to consider what Teas are most in demand or most likely to be in request in his neighborhood and not simply what he has most of. Then making out a list of what he decides to show he should map out in his mind the best manner of arranging the same.

The window display should be frequently altered and the Teas never allowed to remain until they become discolored, stale and dirty, as in such cases instead of attracting trade it will only serve to repel it, and no favorite cats should be allowed to sun themselves near the Tea no matter how sleek or handsome they may be. In emptying the window also each package should be carefully examined, cleaned and replaced in stock, ready for sale and hidden out of sight regardless of its condition. Carelessness in this matter is a source of serious loss.

The Tea salesman of the future must not be illiterate or ignorant of his business; the day for such has gone by in this country, never to return. Any salesman can take orders but very few can impart information about the Teas he sells or tries to sell, so that the customer learns nothing from contact with him, while many of the best purchasers like to talk to an intelligent and well-posted man in order to learn all they can about the article. Again, it is the Tea salesman who knows the meaning and feels the power of what he is talking about that will naturally speak earnestly and with the right emphasis; while otherwise he will not emphasize it at all and very often a good sale of Tea depends on the proper emphasis given to a few important words in reply to the customer's question about the article. The good Tea salesman should speak to explain, convince and persuade and should keep this final object constantly in mind; he should know instantly the effect he is producing on the customer, and the more favorable the effect is the better he can talk, because his faculties are thus encouraged. But when a question can be made clear at all it is made all the clearer by brevity, as all sensible intending purchasers prefer evidence to eloquence.

Many Tea dealers and employees have an idea that a certain kind of smartness in dealing is a praiseworthy business qualification, and that success in the Tea business depends largely on that kind of sharpness and chicanery in dealing with their Tea customers. This is a most mistaken idea, if not worse, as it should be the first and fundamental effort on the part of every business man to gain the respect and confidence of his patrons, not their ill-will and contempt by getting the best of them, as he foolishly supposes. As a customer who once finds himself deceived in either quality or price in buying Teas will consequently be suspicious ever afterward of the dealer who has deceived him, so that the dealer who thought himself so sharp in making a little extra money on the first transaction loses in the end a good and prompt-paying customer who might have traded with him for years if he had but retained his good opinion and induced him by fair dealing to continue his patronage. It has been wisely and sensibly said by President Lincoln that "You may fool some of the people all the time, and all the people some of the time, but you cannot fool all the people all the time." Enduring prosperity in the Tea business cannot be founded on cunning and deception, as the tricky and deceitful Tea dealer is sure to fall a victim sooner or later to the influences which are forever working against him. His business structure is built in sand and its foundations will be certain to give way and crush him in the end. Young men in the line particularly cannot give these truths too much weight and importance, as the future of the young Tea dealer is secure who repudiates every form of deception and double dealing, thereby laying the foundation of his business career on the enduring principles of ever-lasting truth and honest dealing.

A reputation for intelligence and truthfulness is indispensable to a permanent and satisfying success in the Tea business, and politeness is also among the few weapons that the small Tea dealer has at his command to meet the competition of larger dealers who

buy their Teas more cheaply. But the larger the business the greater the number of hands required and consequently the less chance of the customers being treated with deference. That these advantages are not fully realized and utilized by the average retailer is well known to all who come in contact with them. One important point in particular to be impressed upon your assistants is the necessity of careful and polite attention to the smallest customers. There is an old and trite adage which says, "When you buy, keep one eye on the goods and the other on the seller, but when you sell, keep both eyes on the buyer." Customers are drawn to the dealer who greets them cordially, treats them with civility, shows them little courtesies, manifests an interest in their wants and seeks to gain their confidence. Do not imagine that customers consider cheap Teas and "cut prices" are the equivalent for such treatment, for if you do you will soon have to discontinue business for lack of brains or be sold out altogether, although you may charge your misfortune to other causes.

Don't.

Don't smoke in your store or encourage your customers to do so.

Don't let your store smell of mice and rats, or allow dogs or cats around the store.

Don't permit your store to smell of oil, fish, soap, strong cheese or other loud smelling articles.

Don't clean your scales, weights and other utensils or wash your counters and shelves in the presence of customers.

Don't spit on your store floor or allow others to do so, and never be without a clean handkerchief, even when you wear an apron.

Don't use the same set of scales, weights or scoops for sugar, flour, rice, cheese or other articles for Tea, as they invariably impart their odor to it.

Don't store your Teas in damp places or they will soon contract a musty, mildewy smell and flavor, and be careful of wet cellars, which produce the same results.

Don't permit your store to become a lounging place for idlers, local gossipers or cheap politicians, no matter how profitable they may appear to you, as particular customers do not like to have their business exposed to such hangers-on.

Don't have dirty hands, face or wear your fingernails in half-mourning, and don't wear a sour, illtempered face—nothing so repels a sensitive customer —but cultivate a cheerful countenance at all times and under all circumstances. In other words, if you do not possess this virtue at least assume it.

Don't overbuy, as most Teas deteriorate by long keeping, particularly after opening, get dirty, lose strength and therefore become unsalable. And when you happen to get stuck on a bad lot dispose of them quickly and as privately as you can, even at a sacrifice. Above all things don't try to work them off on your customers, either regular or casual, as nothing will ruin your Tea trade quicker or surer.

In conclusion, be thorough in all you undertake, as nothing conduces like thoroughness and sincere earnestness to build up and retain a successful Tea business. And remember that it is much easier to do particular work yourself than to show others how to. Master the whole business and the road to success has been mapped out, as most certainly the dealer who notes what a community is most in need of and supplies that want most thoroughly possesses the attributes of a successful Tea merchant.

Monday, June 23, 2014

Beverages Continued

Below are some additional recipes for common beverages from the 19th Century:

To Make Good Tea.

—In making tea it is usual to allow a teaspoonful of dry tea for each person. First scald the teapot by filling it with boiling water, and letting it stand a few minutes near the fire. Turn off the water and put in the dry tea; over this pour boiling water enough to cover it. Cover the teapot closely, and stand near the fire for five ~minutes. Fill up with boiling water, and serve.

To Make Good Chocolate

—Grate one cake of fine French chocolate, and put it over the fire .

with lukewarm water enough to cover it. Stir gently until thoroughly dissolved. Pour in gradually, stirring all the time, half a pint of boiling milk. Boil all gently for five minutes, and serve.

Chocolate a la FRANCAISE

—Grate one cake of fine French chocolate into a gill of cold milk. Put into a vessel of boiling water, and stir till well mixed. Add half a pint of milk and water, cold, and let it gradually come to a boil, stirring all the time. Boil fifteen minutes.

COCOA SHELLS.

—-Soak a teacupful of dry shells all night in a quart of cold water; boil in the same water three hours before using. (Prepared shells do not require soaking.) Boil them rapidly for one hour, settle and strain, and add boiling milk in the proportion of a pint of milk to a quart of water and three ounces of shells.

BROMA.

-To make broma, powder in a mortar, two ounces of arrowroot, half a pound of loaf sugar, and a pound of pure chocolate. Sifi carefully through a hair sieve. To two tablespoonfuls of this powder put two tablespoonfuls of cream. Stir till well mixed, pour on half a pint of boiling milk, and boil all for ten minutes.

Source: The Godey's Lady's Book Receipts ©1870

To Make Good Tea.

—In making tea it is usual to allow a teaspoonful of dry tea for each person. First scald the teapot by filling it with boiling water, and letting it stand a few minutes near the fire. Turn off the water and put in the dry tea; over this pour boiling water enough to cover it. Cover the teapot closely, and stand near the fire for five ~minutes. Fill up with boiling water, and serve.

To Make Good Chocolate

—Grate one cake of fine French chocolate, and put it over the fire .

with lukewarm water enough to cover it. Stir gently until thoroughly dissolved. Pour in gradually, stirring all the time, half a pint of boiling milk. Boil all gently for five minutes, and serve.

Chocolate a la FRANCAISE

—Grate one cake of fine French chocolate into a gill of cold milk. Put into a vessel of boiling water, and stir till well mixed. Add half a pint of milk and water, cold, and let it gradually come to a boil, stirring all the time. Boil fifteen minutes.

COCOA SHELLS.

—-Soak a teacupful of dry shells all night in a quart of cold water; boil in the same water three hours before using. (Prepared shells do not require soaking.) Boil them rapidly for one hour, settle and strain, and add boiling milk in the proportion of a pint of milk to a quart of water and three ounces of shells.

BROMA.

-To make broma, powder in a mortar, two ounces of arrowroot, half a pound of loaf sugar, and a pound of pure chocolate. Sifi carefully through a hair sieve. To two tablespoonfuls of this powder put two tablespoonfuls of cream. Stir till well mixed, pour on half a pint of boiling milk, and boil all for ten minutes.

Source: The Godey's Lady's Book Receipts ©1870

Friday, June 20, 2014

Amputations

Not a pleasant subject but one our historical characters dealt with on a fairly regular bases.

Amputation of the Arm.

Operation.— Give the patient ninety drops of laudanum, or let him breathe ether from a large ■ponge till sound asleep, and seat him on a narrow and firm table or chest, of a convenient height, so that some one can support him, by clasping him round the body. If the handkerchief and stick have not been previously applied, place it as high up on the arm as possible (the stick being very short) and so that the knot may pass on the inner third of it. Your instruments having been placed regularly on a table or waiter, and within reach of your hand, while some one supports the lower end of the arm, and at the same time draws down the skin, take the large knife and make one straight cut all round the limb, through the skin and fat only, then with the penknife separate as much of the skin from the flesh above the cut, and all round it, as will form a flap to cover the face of the stump; when you think there is enough separated, turn it back, where it must be held by an assistant, while with the large knife you make a second straight incision round the arm and down to the bone, as close as you can to the doubled edge of the flap, but taking great care not to cut it. The bone is now to be passed through the slit in the piece of linen before mentioned, and pressed by its ends against the upper surface of the wound by the person who holds the flap, while you saw through the bone as near to it as you can. With the books or pincers, you then seize and tie up every vessel that bleeds, the largest first, and smaller ones next, until they are all secured. When this is done, relax the stick a little; if an artery springs, tie it as before. The wound is now to be gently cleansed with a sponge and warm water, and the stick to be relaxed. If it is evident that the arteries are all tied, bring the flap over the end of the stump, draw its edges together with strips of sticking-pi as tor, leaving the ligature

hanging out at the angles, lay the piece of linen spread with ointment over the straps, a pledget of lint over that, and secure the whole by the bandage, when the patient may be carried to bed, and the stump laid on a pillow.

The handkerchief and stick are to be left loosely round the limb, so that if any bleeding happens to come on, it may be tightened in an instant by the person who watches by the patient, when the dressings must be taken off, the flap raised, and the vessel be sought for and tied up, after which, every thing must be placed as before.

It may be well to observe that in sawing through the bone, along and free stroke should be used, to prevent any hitching, as an additional security against which, the teeth of the saw should be well sharpened and set wide.

There is also another circumstance, which it is essential to be aware of: the ends of divided arteries cannot at times be got hold of, or being diseased their coats give way under the hook, so that they cannot be drawn out; sometimes also, they are found ossified or turned into bone. In all these cases, having armed a needle with a ligature, pass it through the flesh round the artery, so that when tied, there will be a portion of it included in the ligature along with the artery. When the ligature has been made to encircle the artery, cut off the needle and tie it firmly in the ordinary way.

The bandages, etc., should not be disturbed for five or six days, if the weather is cool; if it is very warm, they may be removed in three. This is to be done with the greatest care, soaking them well with warm water until they are quite soft, and can be taken away without sticking to the stump. A clean, plaster, lint, and bandage are then to be applied as before, to be removed every two days. At the expiration of ten or fifteen days the ligatures generally come away; and in three or four weeks, if every thing goes on well, the wound heals.

Amputation of the Thigh.

This is performed in precisely the same manner as that of the arm, care being used to prevent the edges of the flap from uniting until the surface of the stump has adhered to it.

Amputation of the Leg.

As there are two bones in the leg ,which have to thin muscle .between, it is necessary to have an additional knife to those already mentioned, to divide it. It should have a long narrow blade, with a double-cutting edge, and a sharp point; a carving or case knife may be ground down to answer the purpose, the blade being reduced to rather less than half an inch in width. The linen or leather strip should also have two slits in it instead of one. The patient is to be laid on his back, on a table covered with blankets or a tnatresi*, with a sufficient number of assistants to secure him. The handkerchief and stick being applied on the upper part of the thigh, one person holds the knee, and another the foot and leg as steadily as possible, while with the large knife the operator makes on oblique incision round the limb, through the skin, and, beginning at five or six inches below the knee pan, and carrying it regularly round in such a manner that the cut will be lower down on the culf than in front of the leg. As much of the skin is then to be separated by the penknife as will cover the stump. When this is turned back, a second cut is to be made all round the limb and down to the bones, when, with the narrow-bladcd knife just mentioned, the flesh between them is to be divided. The middle piece of the leather strip is now to be pulled through between the bones, the whole being held back by the assistant, who supports the flap while the bones are sawed, which should be to managed that the smaller one is completely cut through bj the time tbe other is only half so. The arteries are then to be taken up, the Bap brought down and secured by adhesive plasters, etc. as already directed.

Amputation of the Forearm.

The forearm has two bones in it, the narrow bladed knife, and the strip of linen with three taiis. are to be provided. Tbe incision should be straight round the part, as in the arm, with this exception, complete it aa directed fur the preceding case.

Amputation of Fingers and Toes.

Draw the skin back, and make an incision round the finger, a little below the joint it is intended to remove, turn back a little flap to cover the stump, then cut down to the joint, bending it so that voo can cut through the ligaments that connect the two bc.nes, tho under one first, then that on the side. The bead of the bone is then to be turned out, while you cut through the remaining s«a parts. If you see an artery spirt, tie it up, if not, bring down the flap and secure it by a strip of sticking-plaster, and a narrow bandage over the whole.

Source: Mackenzie's Ten Thousand Receipts ©1867

Amputation of the Arm.

Operation.— Give the patient ninety drops of laudanum, or let him breathe ether from a large ■ponge till sound asleep, and seat him on a narrow and firm table or chest, of a convenient height, so that some one can support him, by clasping him round the body. If the handkerchief and stick have not been previously applied, place it as high up on the arm as possible (the stick being very short) and so that the knot may pass on the inner third of it. Your instruments having been placed regularly on a table or waiter, and within reach of your hand, while some one supports the lower end of the arm, and at the same time draws down the skin, take the large knife and make one straight cut all round the limb, through the skin and fat only, then with the penknife separate as much of the skin from the flesh above the cut, and all round it, as will form a flap to cover the face of the stump; when you think there is enough separated, turn it back, where it must be held by an assistant, while with the large knife you make a second straight incision round the arm and down to the bone, as close as you can to the doubled edge of the flap, but taking great care not to cut it. The bone is now to be passed through the slit in the piece of linen before mentioned, and pressed by its ends against the upper surface of the wound by the person who holds the flap, while you saw through the bone as near to it as you can. With the books or pincers, you then seize and tie up every vessel that bleeds, the largest first, and smaller ones next, until they are all secured. When this is done, relax the stick a little; if an artery springs, tie it as before. The wound is now to be gently cleansed with a sponge and warm water, and the stick to be relaxed. If it is evident that the arteries are all tied, bring the flap over the end of the stump, draw its edges together with strips of sticking-pi as tor, leaving the ligature

hanging out at the angles, lay the piece of linen spread with ointment over the straps, a pledget of lint over that, and secure the whole by the bandage, when the patient may be carried to bed, and the stump laid on a pillow.

The handkerchief and stick are to be left loosely round the limb, so that if any bleeding happens to come on, it may be tightened in an instant by the person who watches by the patient, when the dressings must be taken off, the flap raised, and the vessel be sought for and tied up, after which, every thing must be placed as before.

It may be well to observe that in sawing through the bone, along and free stroke should be used, to prevent any hitching, as an additional security against which, the teeth of the saw should be well sharpened and set wide.

There is also another circumstance, which it is essential to be aware of: the ends of divided arteries cannot at times be got hold of, or being diseased their coats give way under the hook, so that they cannot be drawn out; sometimes also, they are found ossified or turned into bone. In all these cases, having armed a needle with a ligature, pass it through the flesh round the artery, so that when tied, there will be a portion of it included in the ligature along with the artery. When the ligature has been made to encircle the artery, cut off the needle and tie it firmly in the ordinary way.

The bandages, etc., should not be disturbed for five or six days, if the weather is cool; if it is very warm, they may be removed in three. This is to be done with the greatest care, soaking them well with warm water until they are quite soft, and can be taken away without sticking to the stump. A clean, plaster, lint, and bandage are then to be applied as before, to be removed every two days. At the expiration of ten or fifteen days the ligatures generally come away; and in three or four weeks, if every thing goes on well, the wound heals.

Amputation of the Thigh.

This is performed in precisely the same manner as that of the arm, care being used to prevent the edges of the flap from uniting until the surface of the stump has adhered to it.

Amputation of the Leg.

As there are two bones in the leg ,which have to thin muscle .between, it is necessary to have an additional knife to those already mentioned, to divide it. It should have a long narrow blade, with a double-cutting edge, and a sharp point; a carving or case knife may be ground down to answer the purpose, the blade being reduced to rather less than half an inch in width. The linen or leather strip should also have two slits in it instead of one. The patient is to be laid on his back, on a table covered with blankets or a tnatresi*, with a sufficient number of assistants to secure him. The handkerchief and stick being applied on the upper part of the thigh, one person holds the knee, and another the foot and leg as steadily as possible, while with the large knife the operator makes on oblique incision round the limb, through the skin, and, beginning at five or six inches below the knee pan, and carrying it regularly round in such a manner that the cut will be lower down on the culf than in front of the leg. As much of the skin is then to be separated by the penknife as will cover the stump. When this is turned back, a second cut is to be made all round the limb and down to the bones, when, with the narrow-bladcd knife just mentioned, the flesh between them is to be divided. The middle piece of the leather strip is now to be pulled through between the bones, the whole being held back by the assistant, who supports the flap while the bones are sawed, which should be to managed that the smaller one is completely cut through bj the time tbe other is only half so. The arteries are then to be taken up, the Bap brought down and secured by adhesive plasters, etc. as already directed.

Amputation of the Forearm.

The forearm has two bones in it, the narrow bladed knife, and the strip of linen with three taiis. are to be provided. Tbe incision should be straight round the part, as in the arm, with this exception, complete it aa directed fur the preceding case.

Amputation of Fingers and Toes.

Draw the skin back, and make an incision round the finger, a little below the joint it is intended to remove, turn back a little flap to cover the stump, then cut down to the joint, bending it so that voo can cut through the ligaments that connect the two bc.nes, tho under one first, then that on the side. The bead of the bone is then to be turned out, while you cut through the remaining s«a parts. If you see an artery spirt, tie it up, if not, bring down the flap and secure it by a strip of sticking-plaster, and a narrow bandage over the whole.

Source: Mackenzie's Ten Thousand Receipts ©1867

Thursday, June 19, 2014

ON SETTING TABLES, AND PREPARING VARIOUS ARTICLES OR FOOD FOR THE TABLE

I love the tidbit about cooling cucumbers in this article. Today we simply take them from the fridge, however back in 1871 that wasn't possible. Enjoy this article from Miss Beecher's Domestic Receipt Book ©1871

ON SETTING TABLES, AND PREPARING VARIOUS ARTICLES OR FOOD FOR THE TABLE.

To a person accustomed to a good table, the manner in which the table is set, and the mode in which food is prepared and set on, has a great influence, not only on the eye, but the appetite. A housekeeper ought, therefore, to attend carefully to these particulars.

The table-cloth should always be white, and well washed and ironed. When taken from the table, it should be folded in the ironed creases, and some heavy article laid on it. A heavy bit of plank, smoothed and kept for the purpose, is useful. By this method, the table-cloth looks tidy much longer than when it is less carefully laid aside.

Where table napkins are used, care should be taken to keep the same one to each person, and, in laying them aside, they should be folded so as to hide the soiled places, and laid under pressure.

The table-cloth should always be put on square, and right side upward. The articles of furniture should be placed as exhibited in figures 7 and 8.

The bread for breakfast and tea should be cut in even, regular slices, not over a fourth of an inch thick, and all crumbs removed from the bread plate. They should be piled in a regular form, and if the slices are large, they should be divided.

The butter should be cooled in cold water, if not already hard, and then cut into a smooth and regular form, and a butter knife be laid by the plate, to be used for no ot her purpose but to help the butter.

Small mats, or cup plates, should be placed at each plate, to receive the tea-cup, when it would otherwise be set upon the table-cloth and stain it .

All the flour should be wiped from small cakes, and the crumbs be kept from the bread plate. In preparing dishes for the dinner-table. all watet should be carefully drained from vegetables, and the edges of the platters and dishes should be made perfectly clean and neat.

All soiled spots should be removed from the outside of pitchers, gravy boats, and every article used on the table; the handles of the knives and forks must be clean, and the knives bright and sharp.

In winter, the plates, and all the dishes used, both for meat and vegetables, should be set to the fire to warm, when the table is being set, as cold plates and dishes cool the vegetables, gravy, and meats, which by many is deemed a great injury.

Cucumbers, when prepared for table, should be laid in cold water for an hour or two to cool, and then be peeled and cut into fresh cold water. Then they should be drained, and brought to the table, and seasoned the last thing.

The water should be drained thoroughly from all greens and salads.

There are certain articles which are usually set on together, because it is the fashion, or because they are suited to each other.

Thus with strong-flavored meats, like mutton, goose, and duck, it is customary to serve the strong-flavored vegetables, such as onions and turnips. Thus, turnips are put in mutton broth, and served with mutton, and onions are used to stuff geese and ducks. But onions are usually banished from the table and from cooking, on account of the disagreeable flavor they impart to the atmosphere and breath.

Boiled Poultry should be accompanied with boiled ham, or tongue.

Boiled Rice is served with poultry as a vegetable.

Jelly is served with mutton, venison, and roasted meats, and is used in the gravies for hashes.

Fresh Pork requires some acid saQce, such as cranberry, or tart apple sauce.

Drawn Butter, prepared as in the receipt, with eggs in it, is used with boiled fowls and boiled fish.

Pickles are served especially with fish, and Soy is a fashionable sauce for fish, which is mixed on the plate with drawn butter.

There are modes of garnishing dishes, and preparing them for table, which give an air of taste and refinement, that pleases the eye.

Thus, in preparing a dish of fricasseed fowls, or stewed fowls. or cold fowls warmed over, small cups of boiled rice can be laid inverted around the edge of the platter, to eat with the meat.

Sweetbreads fried brown in lard, and laid around such a dish, give it a tasteful look.

On Broiled Ham, or Veal, eggs boiled, or fried and laid, one on each piece, look well.

Greens and Asparagus should be well drained, and laid on buttered toast, and then slices of boiled eggs be laid on the top, and around.

Hashes, and preparations of pig's and calve's head and feet, should be laid on toast, and garnished with round slices of lemon.

Curled Parsley, or Common Parsley, is a pretty garnish, to be fastened to the shank of a ham, to conceal the bone, and laid around the dish holding it. It looks well laid around any dish of cold slices of tongue, ham, or meat of any kind.

The proper mode of setting a dinner-table is shown at Fig. 7, and the proper way of setting a tea-table is shown at Fig. 8. In this drawing of a tea-table, smallsized plates are set around, with a knife, napkin, and cup plate laid by each, in a regular manner, while the articles of food are to be set, also, in regular order. On the waiter are placed the tea-cups and saucers, sugar bowl, slop bowl, cream cup, and two or three articles for tea, coffee, and water, as the case may be. This drawing may aid some housekeepers in teaching a domestic how to set a tea-table, as the picture will assist the memory in some cases. On the dinner table, by each plate, is a knife, fork, napkin, and tumbler: on the tea-table by each plate is a knife, napkin, and small cup-platc.

ON SETTING TABLES, AND PREPARING VARIOUS ARTICLES OR FOOD FOR THE TABLE.

To a person accustomed to a good table, the manner in which the table is set, and the mode in which food is prepared and set on, has a great influence, not only on the eye, but the appetite. A housekeeper ought, therefore, to attend carefully to these particulars.

The table-cloth should always be white, and well washed and ironed. When taken from the table, it should be folded in the ironed creases, and some heavy article laid on it. A heavy bit of plank, smoothed and kept for the purpose, is useful. By this method, the table-cloth looks tidy much longer than when it is less carefully laid aside.

Where table napkins are used, care should be taken to keep the same one to each person, and, in laying them aside, they should be folded so as to hide the soiled places, and laid under pressure.

The table-cloth should always be put on square, and right side upward. The articles of furniture should be placed as exhibited in figures 7 and 8.

The bread for breakfast and tea should be cut in even, regular slices, not over a fourth of an inch thick, and all crumbs removed from the bread plate. They should be piled in a regular form, and if the slices are large, they should be divided.

The butter should be cooled in cold water, if not already hard, and then cut into a smooth and regular form, and a butter knife be laid by the plate, to be used for no ot her purpose but to help the butter.

Small mats, or cup plates, should be placed at each plate, to receive the tea-cup, when it would otherwise be set upon the table-cloth and stain it .

All the flour should be wiped from small cakes, and the crumbs be kept from the bread plate. In preparing dishes for the dinner-table. all watet should be carefully drained from vegetables, and the edges of the platters and dishes should be made perfectly clean and neat.

All soiled spots should be removed from the outside of pitchers, gravy boats, and every article used on the table; the handles of the knives and forks must be clean, and the knives bright and sharp.

In winter, the plates, and all the dishes used, both for meat and vegetables, should be set to the fire to warm, when the table is being set, as cold plates and dishes cool the vegetables, gravy, and meats, which by many is deemed a great injury.

Cucumbers, when prepared for table, should be laid in cold water for an hour or two to cool, and then be peeled and cut into fresh cold water. Then they should be drained, and brought to the table, and seasoned the last thing.

The water should be drained thoroughly from all greens and salads.

There are certain articles which are usually set on together, because it is the fashion, or because they are suited to each other.

Thus with strong-flavored meats, like mutton, goose, and duck, it is customary to serve the strong-flavored vegetables, such as onions and turnips. Thus, turnips are put in mutton broth, and served with mutton, and onions are used to stuff geese and ducks. But onions are usually banished from the table and from cooking, on account of the disagreeable flavor they impart to the atmosphere and breath.

Boiled Poultry should be accompanied with boiled ham, or tongue.

Boiled Rice is served with poultry as a vegetable.

Jelly is served with mutton, venison, and roasted meats, and is used in the gravies for hashes.

Fresh Pork requires some acid saQce, such as cranberry, or tart apple sauce.

Drawn Butter, prepared as in the receipt, with eggs in it, is used with boiled fowls and boiled fish.

Pickles are served especially with fish, and Soy is a fashionable sauce for fish, which is mixed on the plate with drawn butter.

There are modes of garnishing dishes, and preparing them for table, which give an air of taste and refinement, that pleases the eye.

Thus, in preparing a dish of fricasseed fowls, or stewed fowls. or cold fowls warmed over, small cups of boiled rice can be laid inverted around the edge of the platter, to eat with the meat.

Sweetbreads fried brown in lard, and laid around such a dish, give it a tasteful look.

On Broiled Ham, or Veal, eggs boiled, or fried and laid, one on each piece, look well.

Greens and Asparagus should be well drained, and laid on buttered toast, and then slices of boiled eggs be laid on the top, and around.

Hashes, and preparations of pig's and calve's head and feet, should be laid on toast, and garnished with round slices of lemon.

Curled Parsley, or Common Parsley, is a pretty garnish, to be fastened to the shank of a ham, to conceal the bone, and laid around the dish holding it. It looks well laid around any dish of cold slices of tongue, ham, or meat of any kind.

The proper mode of setting a dinner-table is shown at Fig. 7, and the proper way of setting a tea-table is shown at Fig. 8. In this drawing of a tea-table, smallsized plates are set around, with a knife, napkin, and cup plate laid by each, in a regular manner, while the articles of food are to be set, also, in regular order. On the waiter are placed the tea-cups and saucers, sugar bowl, slop bowl, cream cup, and two or three articles for tea, coffee, and water, as the case may be. This drawing may aid some housekeepers in teaching a domestic how to set a tea-table, as the picture will assist the memory in some cases. On the dinner table, by each plate, is a knife, fork, napkin, and tumbler: on the tea-table by each plate is a knife, napkin, and small cup-platc.

Wednesday, June 18, 2014

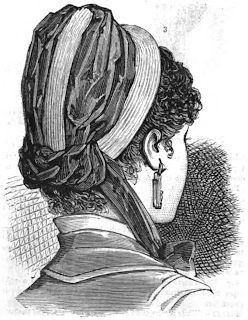

1879 Historical Fashions

Today we are featuring 1879 images of ladies fashions.

Dresses

Walking Dress

House Dress

Bathing Suits

Bonnets

Dresses

Walking Dress

House Dress

Bathing Suits

Bonnets

Tuesday, June 17, 2014

1872 - 1880 Wages

Every so often as an author I'm looking for the price of various items during the year I'm writing. I generally find advertisements with sale prices as a guide. This tidbit comes from Massachusetts it does give an understanding to the various wages from 1872 - 1880. Perhaps you'll find it helpful too.

Monday, June 16, 2014

Beverages

Below are several recipes and instructions for making various common beverages from 1867. Along with details about coffee, the beans and some of the various types known then.

TO MAKE PUNCH.

For a gallon of punch take six fresh Sicily lemons; rub the outsides of them well over with lumps of double-refined loaf-sugar, until they become quite yellow; throw the lumps into the bowl; roll your lemons well on a clean plate or table; cut them in half and squeeze them with a proper instrument over the sugar; bruise the sugar, and continue to add fresh portions of it, mixing the lemon pulp and juice well with it. Much of the goodness of the punch will dc]>end upon this. The quantity of sugar to be added should be great enough to render the mixture without water pleasant to the palate even of a child. When this is obtained, add gradually a small quantity of hot water, just enough to render the syrup thin enough to pass through the strainer. Mix all well together, strain it, and try if there be sugar enough; if at all sour add more. When cold put in a little cold water, and equal quantities of the best cogniac brandy and old Jamaica rum, testing its strength by that infallible guide the palate, A glass of calves'-foot jelly added to the syrup when warm will not injure its qualities.