Preserving meat took a lot of thought and effort on our 19th Century Characters or Ancestors. Below are some recipes for Pickling Beef. Don't think in terms of sweet or dill pickles. Remember pickling was a form of curing meat, as was salting and drying.

PICKLING BEEF —Rub a quarter of a pound of saltpetre and a little brown sugar on the beef; the following day season it with half a pound of bay salt, one ounce of black pepper, one ounce of allspice. Let the beef lie in pickle fourteen days, turning it every day, adding a little common salt three times per week ; then wash it, and put it into a glazed earthen pipkin, deep enough to cover it. Lay beef suet under it; add one pint of water, cover the top with paste and then paper, or with a plate instead of paste. Bake seven hours in an oven; pour off the liquor, but do not cut till cold. Will keep three months.

Source: The Godey's Lady's Book Receipts and Household Hints ©1870

RECIPE FOR PICKLING BEEF, PORK, OR MUTTON

4 gallons of water, 1% lbs. brown sugar, 2 oz. saltpetre, 5 lbs. alum salt. Put the whole into a kettle and let it boil, taking off the scum as it rises with care. When the scum ceases to rise, take it off the fire and let it get cold. Put the meat into the vessel in which it is to be kept and pour in the liquor until it is entirely covered. Beef preserved in this way is as good as if salted, but three days, at the end of 10 weeks. lf the meat is to be kept a long time, the pickle must be boiled and skimmed once in 2 weeks.

PICKLE FOR BEEF, MUTTON, OR PORK

8 gallons of water, 3 lbs. of sugar, 14 lb. saltpetre, 12 lbs. of salt. To be boiled and skimmed until no scum arises. Then pour it cold upon the meat.

PICKLE FOR BEEF

Pack down your beef, sprinkling some fine salt on the parts which come in contact with each other. Place a weight upon the beef and then cover it completely with the pickle made of the following preparations: 12 lbs. of fine Liverpool salt, 8 gallons of water, 1 lb. sugar, and 4 ozs. of saltpetre. Mix the pickle with cold water, skim it well and put it on cold.

l. S. Lewis to J. P. Norris, April 18th, 1822

PICKLED BEEF

6 gallons of water, 12 lbs. of salt, 5 oz. saltpetre, and 6 lbs. of brown sugar. Simmer them over the fire until the scum ceases to rise. This quantity is sufficient for 200 lbs. of beef. Let it stay in pickle 4 or 5 weeks and re-pack it once in that time.

M. Newbold, N. J.

MRS. R. COLEMAN'S RECIPE FOR

PICKLING BEEF OR PORK OF 90 LBS.

6 gallons of water, 9 lbs. of salt, (4y2 of fine and 4% of coarse salt), 3 lbs. brown sugar, 3 oz. saltpetre and 1 oz. of pearl ash. To be boiled and well skimmed and 1 quart of molasses.

90 LBS. OF BEEF OR PORK

The same as the above without the molasses. To be mixed with cold water and well boiled and skimmed.

CORNED BEEF

1 gallon of water, 1% lbs. of salt, y2 lb. brown sugar, and % oz. saltpetre. Boil all together and skim it well. Then put it into a large tub to cool, and when perfectly cold, pour it over your beef or pork and let it remain in four weeks. The meat must be well covered and should not be put down for at least 2 days after killing during which time it should be slightly sprinkled with powdered saltpetre. Mrs. Brown

Source: Cook Book 1st Vol. ©1855

Will you please give me a good recipe for pickling beef—one that you know has been thoroughly tried!

Answer.—The following we know to be good: Cut the beef in convenient pieces and salt down as usual, adding a “pinch” of saltpeter to each piece. Let it remain in salt three days; then drain off the bloody brine formed by the salt, wipe each piece with a clean cloth and re-pack in the tub or other vessel used; a syrup or molasses cask will answer, but not a whisky barrel. For the brine, take as much water as will cover the beef; add salt until no more will disso‘ve; a tea-cup of ground saltpetre and a quart of molasses, or its equivalent of brown sugar. Boil and skim well. When the brine thus prepared is entirely cold, pour it over the beef and keep the latter well pressed under the brine. These proportions are for 200 pounds of beef. If the brine should mould in warm weather, reboil and skim it, adding half pound of cooking soda,and when cold return to the beef.

Source: The Southern Cultivator and Industrial Journal ©1888

The 19th century was full of innovation, exploration and is one of the most popular eras for writing historical fiction. This blog is dedicated to tiny tidbits of information that will help make your novel seem more real to the time period.

Friday, February 27, 2015

Thursday, February 26, 2015

Oregon Trail

From time to time I'll put together a post that list links from my blog on one topic, today I've put together links on the Oregon Trail. Enjoy!

The Oregon Trail

Oregon Trail Outfits

Hob Nailed Shoes

Chinook Jargon Part 1

Chinook Jargon Part 2

First Major Wagon Train

For other links involving Wagon Train and Expansion take a look at Wagon Train Prairie Resources that I put together last year.

The Oregon Trail

Oregon Trail Outfits

Hob Nailed Shoes

Chinook Jargon Part 1

Chinook Jargon Part 2

First Major Wagon Train

For other links involving Wagon Train and Expansion take a look at Wagon Train Prairie Resources that I put together last year.

Wednesday, February 25, 2015

1877 Fashions

1877 fashions from original sources:

Riding Habit Back and Front

Chemise

Children

Garden Hat

Traveling Hat

Bonnet

Riding Habit Back and Front

Chemise

Children

Garden Hat

Traveling Hat

Bonnet

Tuesday, February 24, 2015

Sanitariums

Today when someone goes to a Sanitarium it is usually for medical needs. However, the use of the word was a bit different during the 19th Century. Below are four sample advertisement for various sanitariums. From these advertisements you'll see that these were places to go for respite and even a vacation. Below the advertisements are some comments about staying at various sanitariums. So as a writer of historical fiction you might want to add something about Sanitariums in your next novel. Or perhaps a mystery or a romance ensues at one. Have fun writing.

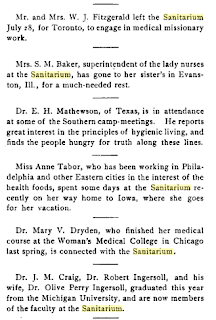

Below are some comments about staying in or visitors to Mission Sanitariums.

Below are some comments about staying in or visitors to Mission Sanitariums.

Monday, February 23, 2015

1873 Cost of living in Tallahassee, FL.

I stumbled on this interesting tidbit about the cost of living in Tallahassee while helping someone else with the cost of living in Florida. Take a look at the cost of beef? A wee bit different than the prices we are paying today.

The cost of living in Tallahassee is perhaps as little as any other place of the same size in the southern country. The market is supplied with good beef, mutton and pork, at from 8 to 12 cents per pound. Poultry of all kinds at moderate prices and plentiful. Oysters in winter in any quantity at 11.50 per bbl., and fish from the coast, such as mullet, sheepshead, speckled trout, bass, flounders, &c., &c., at very low prices, are brought fresh every day. Surrounded by fertile lands there is never a scarcity of fresh garden vegetables of all kinds, in their season.

The society of the place is excellent. True, many changes have taken place of late years. Some of the best citizens have moved away, but there are still left quite a number who give character to the city for hospitality and sociability, and they will always be found ready to extend the hand of friendship to all such new-comers as come for legitimate purposes and know how to behave themselves without regard to their place of nativity. In short, I know of no more agreeable place to spend a winter or to locate for life.

The climate of Leon county, although it is not tropical, is mild and pleasant in winter. Although we frequently have frost, and ice occasionally, yet it is rare for the thermometer to go below 40 deg. Fahr., and then only for a short time, while one would feel comfortable in summer clothing at least one half of our winter. In the summer the thermometer rarely , indicates a greater heat than 96 deg. F. in the shade, and the average in the middle of our August days is not above 90 deg. This heat is tempered by the almost constant sea breeze, the influence of which is distinctly felt. The nights are invariably pleasant, and even in the hottest part of the season some covering is generally necessary to comfortable sleeping.

Source: The Florida Settler ©1873

The cost of living in Tallahassee is perhaps as little as any other place of the same size in the southern country. The market is supplied with good beef, mutton and pork, at from 8 to 12 cents per pound. Poultry of all kinds at moderate prices and plentiful. Oysters in winter in any quantity at 11.50 per bbl., and fish from the coast, such as mullet, sheepshead, speckled trout, bass, flounders, &c., &c., at very low prices, are brought fresh every day. Surrounded by fertile lands there is never a scarcity of fresh garden vegetables of all kinds, in their season.

The society of the place is excellent. True, many changes have taken place of late years. Some of the best citizens have moved away, but there are still left quite a number who give character to the city for hospitality and sociability, and they will always be found ready to extend the hand of friendship to all such new-comers as come for legitimate purposes and know how to behave themselves without regard to their place of nativity. In short, I know of no more agreeable place to spend a winter or to locate for life.

The climate of Leon county, although it is not tropical, is mild and pleasant in winter. Although we frequently have frost, and ice occasionally, yet it is rare for the thermometer to go below 40 deg. Fahr., and then only for a short time, while one would feel comfortable in summer clothing at least one half of our winter. In the summer the thermometer rarely , indicates a greater heat than 96 deg. F. in the shade, and the average in the middle of our August days is not above 90 deg. This heat is tempered by the almost constant sea breeze, the influence of which is distinctly felt. The nights are invariably pleasant, and even in the hottest part of the season some covering is generally necessary to comfortable sleeping.

Source: The Florida Settler ©1873

Friday, February 20, 2015

Underground Railroad in Niagara Region

Below are some excerpts from "Old Trails on the Niagara Frontier" ©1899 There is an entire chapter relating to the underground railroad connections with the Niagara region as well as other history of the trails during the 19th century such as the war of 1812. It's an interesting resource and fires up all kinds of historical scenarios for our characters to be a part of.

It is impossible to state even approximately the number of refugee negroes who crossed by these routes to Upper Canada, now Ontario. In 1844 the number was estimated at 40,000 ;l in 1852 the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada stated in its annual report that there were about 30,000 blacks in Canada West; in 1858 the number was estimated as high as 75,000.' This figure is probably excessive ; but since the negroes continued to come, up to the hour of the Emancipation Proclamation, it is probably within the fact to say that more than 50,000 crossed to Upper Canada, nearly all from points on Lake Erie, the Detroit and Niagara rivers.

Runaway slaves appeared in Buffalo at least as early as the '30's. "Professor Edward Orton recalls that in 1838, soon after his father moved to Buffalo, two sleigh-loads of negroes from the Western Reserve were brought to the house in the night-time; and Mr. Frederick Nicholson of Warsaw, N. Y., states that the Underground work in his vicinity began in 1840. From this time on there was apparently no cessation of migra tions of fugitives into Canada at Black Rock, Buffalo and other points."3 Those too were the days of much passenger travel on Lake Erie, and certain boats came to be known as friendly to the Underground cause. One boat which ran between Cleveland and Buffalo gave employment to the fugitive William Wells Brown. It became known at Cleveland that Brown would take escaped slaves under his protection without charge, hence he rarely failed to find a little company ready to sail when he started out from Cleveland. "In the year 1842," he says, "I conveyed from the 1st of May to the 1st of December, sixty-nine fugitives over Lake Erie to Canada.''' Many anecdotes are told of the search for runaways on the lake steamers. Lake travel in the ante-bellum days was ever liable to be enlivened by an exciting episode in a "nigger-chase"; but usually, it would seem, the negroes could rely upon the friendliness of the captains for concealment or other assistance.

There are chronicled, too, many little histories of flights which brought the fugitive to Buffalo. I pass over those which are readily accessible elsewhere to the student of this phase of our home history.' It is well, however, to devote a paragraph or two to one famous affair which most if not all American writers on the Underground Railroad appear to have overlooked.

One day in 1836 an intelligent negro, riding a thoroughbred but jaded horse, appeared on the streets of Buffalo. His appearance must have advertised him to all as a runaway slave. I do not know that he made any attempt to conceal the fact. His chief concern was to sell the horse as quickly as possible, and get across to Canada. And there, presently, we find him, settled at historic old Niagara, near the mouth of the river. Here, even at that date, so many negroes had made their way from the South, that more than 400 occupied a quarter known as Negro Town. The newcomer, whose name was Moseby, admitted that he had run away from a plantation in Kentucky, and had used a horse that formerly belonged to his master to make his way North. A Kentucky grand jury soon found a true bill against him for horse-stealing, and civil officers traced him to Niagara, and made requisition for his arrest and extradition. The year before, Sir Francis Bond Head had succeeded Sir John Colborne as Governor of Canada West, and before him the case was laid. Sir Francis regarded the charge as lawful, notwithstanding the avowal of Moseby's owners that if they could get him back to Kentucky they would "make an example of him "; in plainer words, would whip him to death as a warning to all slaves who dared to dream of seeking freedom in Canada.

Moseby was arrested and locked up in the Niagara jail; whereupon great excitement arose, the blacks and many sympathizing whites declaring that he should never be carried back South. The Governor, Sir Francis, was petitioned not to surrender Moseby; he replied that his duty was to give him up as a felon, "although he would have armed the province to protect a slave.'' For more than a week crowds of negroes, men and women, camped before the jail, day and night. Under the leadership of a mulatto schoolmaster named Holmes, and of Mrs. Carter, a negress with a gift for making fiery speeches, the mob were kept worked up to a high pitch of excitement, although, as a contemporary writer avers, they were unarmed, showed "good sense, forbearance and resolution,'' and declared their intention not to commit any violence against the English law. They even agreed that Moseby should remain in jail until they could raise the price of the horse, but threatened, "if any attempt were made to take him from the prison, and send him across to Lewiston, they would resist it at the hazard of their lives." The order, however, came for Moseby's delivery to the slave-hunters, and the sheriff and a party of constables attempted to execute it. Moseby was brought out from the jail, handcuffed and placed in a cart; whereupon the mob attacked the officers. The military was called out to help the civil force and ordered to fire on the assailants. Two negroes were killed, two or three wounded, and Moseby ran off and was not pursued. The negro women played a curiously-prominent part in the affair. "They had been most active in the fray, throwing themselves fearlessly between the black men and the whites, who, of course, shrank from injuring them. One woman had seized the sheriff, and held him pinioned in her arms; another, on one of the artillery-men presenting his piece, and swearing that he would shoot her if she did not get out of his way, gave him only one glance of unutterable contempt, and with one hand knocking up his piece, and colkring him with the other, held him in such a manner as to prevent his firing.

Soon after, in the same year, the Governor of Kentucky made requisition on the Governor of the province of Canada West for the surrender of Jesse Happy, another runaway slave, also on a charge of horse-stealing. Sir Francis held him in confinement in Hamilton jail, but refused to deliver him up until he had laid the case before the Home Government. In a most interesting report to the Colonial Secretary, under date of Toronto, Oct. 8, 1837, he asked for instructions "as a matter of general policy," and reviewed the Moseby case in a fair and broad spirit, highly creditable to him alike as an administrator and a friend of the oppressed. "I am by no means desirous," he wrote, '' that this province should become an asylum for the guilty of any color; at the same time the documents submitted with this dispatch will I conceive show that the subject of giving up fugitive slaves to the authorities of the adjoining republican States is one respecting which it is highly desirable I should receive from Her Majesty's Government specific instructions. . It may be argued that the slave escaping from bondage on his master's horse is a vicious struggle between two guilty parties, of which the slave-owner is not only the aggressor, but the blackest criminal of the two. It is a case of the dealer in human flesh versus the stealer of horse-flesh; and it may be argued that, if the British Government does not feel itself authorized to pass judgment on the plaintiff, neither should it on the defendant.'' Sir Francis continues in this ingenious strain, observing that "it is as much a theft in the slave walking from slavery to liberty in his master's shoes as riding on his master's horse." To give up a slave for trial to the American laws, he argued, was in fact giving him back to his former master; and he held that, until the State authorities could separate trial from unjust punishment, however willing the Government of Canada might be to deliver up a man for trial, it was justified in refusing to deliver him up for punishment, "unless sufficient security be entered into in this province, that the person delivered up for trial shall be brought back to Upper Canada as soon as his trial or the punishment awarded by it shall be concluded." And he added this final argument, begging that instructions should be sent to him at once:

It is argued, that the republican states have no right, under the pretext of any human treaty, to claim from the British Government, which does not recognize slavery, beings who by slave-law are not recognized as men and who actually existed as brute beasts in moral darkness, until on reaching British soil they suddenly heard, for the first time in their lives, the sacred words, "Let there be light; and there was light!" From that moment it is argued they were created nun, and if this be true, it is said they cannot be held responsible for conduct prior to their existence.

Sir Francis left the Home Government in no doubt as to his own feelings in the matter; and although I have seen no further report regarding Jesse Happy, neither do I know of any case in which a refugee in Canada for whom requisition was thus made was permitted to go back to slavery. It did sometimes happen, however, that refugees were enticed across the river on one pretext or another, or grew careless and took their chances on the American side, only to fall into the clutches of the ever-watchful slave-hunters.

It is impossible to state even approximately the number of refugee negroes who crossed by these routes to Upper Canada, now Ontario. In 1844 the number was estimated at 40,000 ;l in 1852 the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada stated in its annual report that there were about 30,000 blacks in Canada West; in 1858 the number was estimated as high as 75,000.' This figure is probably excessive ; but since the negroes continued to come, up to the hour of the Emancipation Proclamation, it is probably within the fact to say that more than 50,000 crossed to Upper Canada, nearly all from points on Lake Erie, the Detroit and Niagara rivers.

Runaway slaves appeared in Buffalo at least as early as the '30's. "Professor Edward Orton recalls that in 1838, soon after his father moved to Buffalo, two sleigh-loads of negroes from the Western Reserve were brought to the house in the night-time; and Mr. Frederick Nicholson of Warsaw, N. Y., states that the Underground work in his vicinity began in 1840. From this time on there was apparently no cessation of migra tions of fugitives into Canada at Black Rock, Buffalo and other points."3 Those too were the days of much passenger travel on Lake Erie, and certain boats came to be known as friendly to the Underground cause. One boat which ran between Cleveland and Buffalo gave employment to the fugitive William Wells Brown. It became known at Cleveland that Brown would take escaped slaves under his protection without charge, hence he rarely failed to find a little company ready to sail when he started out from Cleveland. "In the year 1842," he says, "I conveyed from the 1st of May to the 1st of December, sixty-nine fugitives over Lake Erie to Canada.''' Many anecdotes are told of the search for runaways on the lake steamers. Lake travel in the ante-bellum days was ever liable to be enlivened by an exciting episode in a "nigger-chase"; but usually, it would seem, the negroes could rely upon the friendliness of the captains for concealment or other assistance.

There are chronicled, too, many little histories of flights which brought the fugitive to Buffalo. I pass over those which are readily accessible elsewhere to the student of this phase of our home history.' It is well, however, to devote a paragraph or two to one famous affair which most if not all American writers on the Underground Railroad appear to have overlooked.

One day in 1836 an intelligent negro, riding a thoroughbred but jaded horse, appeared on the streets of Buffalo. His appearance must have advertised him to all as a runaway slave. I do not know that he made any attempt to conceal the fact. His chief concern was to sell the horse as quickly as possible, and get across to Canada. And there, presently, we find him, settled at historic old Niagara, near the mouth of the river. Here, even at that date, so many negroes had made their way from the South, that more than 400 occupied a quarter known as Negro Town. The newcomer, whose name was Moseby, admitted that he had run away from a plantation in Kentucky, and had used a horse that formerly belonged to his master to make his way North. A Kentucky grand jury soon found a true bill against him for horse-stealing, and civil officers traced him to Niagara, and made requisition for his arrest and extradition. The year before, Sir Francis Bond Head had succeeded Sir John Colborne as Governor of Canada West, and before him the case was laid. Sir Francis regarded the charge as lawful, notwithstanding the avowal of Moseby's owners that if they could get him back to Kentucky they would "make an example of him "; in plainer words, would whip him to death as a warning to all slaves who dared to dream of seeking freedom in Canada.

Moseby was arrested and locked up in the Niagara jail; whereupon great excitement arose, the blacks and many sympathizing whites declaring that he should never be carried back South. The Governor, Sir Francis, was petitioned not to surrender Moseby; he replied that his duty was to give him up as a felon, "although he would have armed the province to protect a slave.'' For more than a week crowds of negroes, men and women, camped before the jail, day and night. Under the leadership of a mulatto schoolmaster named Holmes, and of Mrs. Carter, a negress with a gift for making fiery speeches, the mob were kept worked up to a high pitch of excitement, although, as a contemporary writer avers, they were unarmed, showed "good sense, forbearance and resolution,'' and declared their intention not to commit any violence against the English law. They even agreed that Moseby should remain in jail until they could raise the price of the horse, but threatened, "if any attempt were made to take him from the prison, and send him across to Lewiston, they would resist it at the hazard of their lives." The order, however, came for Moseby's delivery to the slave-hunters, and the sheriff and a party of constables attempted to execute it. Moseby was brought out from the jail, handcuffed and placed in a cart; whereupon the mob attacked the officers. The military was called out to help the civil force and ordered to fire on the assailants. Two negroes were killed, two or three wounded, and Moseby ran off and was not pursued. The negro women played a curiously-prominent part in the affair. "They had been most active in the fray, throwing themselves fearlessly between the black men and the whites, who, of course, shrank from injuring them. One woman had seized the sheriff, and held him pinioned in her arms; another, on one of the artillery-men presenting his piece, and swearing that he would shoot her if she did not get out of his way, gave him only one glance of unutterable contempt, and with one hand knocking up his piece, and colkring him with the other, held him in such a manner as to prevent his firing.

Soon after, in the same year, the Governor of Kentucky made requisition on the Governor of the province of Canada West for the surrender of Jesse Happy, another runaway slave, also on a charge of horse-stealing. Sir Francis held him in confinement in Hamilton jail, but refused to deliver him up until he had laid the case before the Home Government. In a most interesting report to the Colonial Secretary, under date of Toronto, Oct. 8, 1837, he asked for instructions "as a matter of general policy," and reviewed the Moseby case in a fair and broad spirit, highly creditable to him alike as an administrator and a friend of the oppressed. "I am by no means desirous," he wrote, '' that this province should become an asylum for the guilty of any color; at the same time the documents submitted with this dispatch will I conceive show that the subject of giving up fugitive slaves to the authorities of the adjoining republican States is one respecting which it is highly desirable I should receive from Her Majesty's Government specific instructions. . It may be argued that the slave escaping from bondage on his master's horse is a vicious struggle between two guilty parties, of which the slave-owner is not only the aggressor, but the blackest criminal of the two. It is a case of the dealer in human flesh versus the stealer of horse-flesh; and it may be argued that, if the British Government does not feel itself authorized to pass judgment on the plaintiff, neither should it on the defendant.'' Sir Francis continues in this ingenious strain, observing that "it is as much a theft in the slave walking from slavery to liberty in his master's shoes as riding on his master's horse." To give up a slave for trial to the American laws, he argued, was in fact giving him back to his former master; and he held that, until the State authorities could separate trial from unjust punishment, however willing the Government of Canada might be to deliver up a man for trial, it was justified in refusing to deliver him up for punishment, "unless sufficient security be entered into in this province, that the person delivered up for trial shall be brought back to Upper Canada as soon as his trial or the punishment awarded by it shall be concluded." And he added this final argument, begging that instructions should be sent to him at once:

It is argued, that the republican states have no right, under the pretext of any human treaty, to claim from the British Government, which does not recognize slavery, beings who by slave-law are not recognized as men and who actually existed as brute beasts in moral darkness, until on reaching British soil they suddenly heard, for the first time in their lives, the sacred words, "Let there be light; and there was light!" From that moment it is argued they were created nun, and if this be true, it is said they cannot be held responsible for conduct prior to their existence.

Sir Francis left the Home Government in no doubt as to his own feelings in the matter; and although I have seen no further report regarding Jesse Happy, neither do I know of any case in which a refugee in Canada for whom requisition was thus made was permitted to go back to slavery. It did sometimes happen, however, that refugees were enticed across the river on one pretext or another, or grew careless and took their chances on the American side, only to fall into the clutches of the ever-watchful slave-hunters.

Thursday, February 19, 2015

Sod House

While I was researching information on the construction of a sod house, I discovered this delightful account that is very informative. I hope you gain as much as I have from it. This was published in the Ladies Repository in 1876.

THE gold fever of 1859-60, and the consequent rush across the Plains, established a line of sod-houses from the Missouri River to the Rocky Mountains, which have developed one of the most important sections of our country, and opened the door of thousands of comfortable and substantial homes to the honest homesteaders of the West. Fifteen years ago, the belt of country lying between the Rocky Mountains, on the west, and the Missouri River, on the east, and stretching indefinitely north and south, was considered as a worthless waste, a treeless, uninhabitable section, without soil, building material, water, or protection against the biting, blinding storms of Winter, which swept furiously down from the mountain fastnessess of the great unexplored, uninvaded home of the storm king of North America. Today the sod-house, the advance-guard of civilization and enterprise in the extreme West, has developed the agricultural adaptability of the Western Desert, invaded and made public the secret domain of the vEolus of our continent, furnished homes and fortunes to hundreds of thousands of God's children, and developed, by its own peculiar adaptability, the resources and wealth of an important section of our country, the great grain and stock producing region of the Missouri Valley. What the log-hut was to the early settlers of New England, the sod

house, "doby," or "dug-out," has been to the pioneer on the prairies of the Missouri Valley. The same force of circumstances which gave the log-house an important position in the history of the eastern half of our great country, has made the sod dwelling an equally important factor in the development of the western portion, and entitled it to a place beside its earlier, but scarcely less substantial or respectable, brother at the Centennial Exposition, and in the history of the great country of countries, the home of the honest toiler, of whatever race or condition.

Strange as it may appear to those unacquainted with the fact, there are tens, perhaps hundreds, of thousands of people in the Missouri Valley, living to-day in houses of sod, turf taken from God's green sward of the great West, laid up with mortar which nature kindly furnishes prepared, and plastered inside with the sandy loam which underlies the black alluvium from which the varied vegetation springs. Within these homes, comfortable beyond the log or frame house of the timbered regions, and equally cleanly and healthful, families are reared, the elements of education dispensed, seeds of piety sown, and the foundation of future fame and fortune successfully laid. Beneath their fostering influence the great fertile but treeless plains have been brought under cultivation, the elements have been made subject to the wants of mankind, towns have sprung up in the uninhabited waste, the iron horse has been called to his duty in their domain, the great agricultural wealth of the country developed, and the desert made to blossom as the rose. To the sod-house of the West belongs honors innumerable, belongs the credit of the thrift and prosperity with which the Missouri Valley is to-day graced and made happy.

It was my fortune, in 1859, to visit the then uninhabited and almost unknown section west of the Missouri, and to witness the construction and practical test of the then novelty, a dwelling composed of turf from the surrounding prairies. It has been my fortune since to watch, with a considerable degree of interest, the development of this to be great grain and stock belt of the Union, and to note, with the care which its novelty and peculiarities suggested, the influence which this great factor, the sod-house, has had in determining the growth and importance of the country. The cry of gold in the Pike's Peak region drew, at the date mentioned, large numbers of people thither, to supply whom with food became the business of the settlers then scattered along the Missouri River, within a few miles of its waters, and in reach of the scanty forests with which its banks are fringed. All provisions, clothing, and mining accouterments were freighted across this then uninhabited section, nearly a thousand miles in width, by teams of horses and cattle. Along the roads which these freighters had laid out, and which all the travel followed, enterprising "ranchemen," bent upon securing a portion of the profits of the season, established themselves for the sale of needed articles to the freighters, whose trips then occupied months instead of, as now, days, and for furnishing meals to the passengers on the stage-coaches, a line of which had been early established. The tents and temporary shelters, which these caterers had provided themselves, soon becoming insufficient, they cast

about for some more commodious and substantial shelters for themselves and guests, the numbers of which were rapidly increasing. In the earlier days of military rule in that region, many of the buildings at Forts Kearney, Leavenworth, and other military posts, had, for want of timber, been constructed of adobe, or sun-dried bricks, the art of making which had been learned from the Mexicans, with whom the military on the western plains had been brought in contact. These were used in some instances by the ranchemen, until the idea of using sods instead suggested itself to the inventive genius of the necessitated housebuilder, and the sod-house became a success. The method, source, and result of the two were so nearly related that the name of adobe, or "doby," as it was every-where known, which properly belonged to the sun-dried bricks, was also given the sod; and henceforth the sod, or "doby," house became an important element of life in the Missouri Valley.

Constant association or familiarity with "doby" failed, in this instance, to breed contempt; and the Missouri Valley settler, who, in freighting his farm products across the plains (and nearly everyone did so), became more thoroughly acquainted with and accustomed to the sod-house, came to recognize its value, and to look upon it as a valuable aid in the economy of prairie life. Those who had substantial wooden homes on the Missouri so far recognized the practical value of "doby" as to make immediate use of the principle on their farms, in the construction of sod out-houses, and various buildings which they might chance to need; and thus the sod-house took another step in advance, and demonstrated its practical utility and durability beside its more pretentious wooden prototype. From this point the transition was easy. The son, who had grown up familiar with the "doby," and been thoroughly convinced of its use and durability, becoming of age, and desirous of erecting a claim shanty on government land, and making a homestead his own by a temporary residence a few days of each year thereon, readily adopted the sod-house as a visible habitation, the material for which was convenient, and the practicabihty thoroughly tested. Later, when the want for a permanent home came about, with the fashion already inaugurated, and the practicability and cheapness especially apparent, there was little difficulty in the adoption of doby as the material for a dwelling, and the home to which the willing, true - hearted, devoted bride was borne. Of the hundreds of thousands of young couples who have made their homes on the prairies of the Missouri Valley, probably more than half owe their first home together, and much of their success, to doby.

The method of construction is not unlike that of the brick dwelling, except that mortar is not always used in laying the sods. A "breaking" plow, such as is used in subduing prairie-grass, and preparing the soil for cultivation, turns the sod in strips, perhaps a foot in width, and of indefinite length. They are then cut in pieces about two and a half feet long, by means of a spade, and are ready for the wall. They are laid up with as much care and nicety as the native skill of the builder can produce, and the edges carefully trimmed with a sharp spade, so that the wall, when completed, is as smooth, and, after being thoroughly dried, is also equally as solid as a brick wall. Window and door frames are set in as in the construction of brick buildings, and the houses are covered sometimes with shingles, sometimes with a thatch of the long prairie grass from the low grounds, and sometimes with several layers of sod cut to turn the rain and make tight joints. Frequently they are divided into several rooms by walls of sod, and occasionally they are two or more stones in height; but usually they are built but one story in height, and with only one room, which is subdivided by light wooden partitions, or in some cases by blankets. The walls, when completed, are plastered smoothly inside, and, being thoroughly whitewashed, present a neat and eminently

healthful and cleanly appearance. The "best room" is papered and carpeted, the walls adorned with pictures, while the vines trained about the door and windows lend their cheerful and refining influence, and the whole, when once inside and the idea of "sod-house" forgotten, has a homelike and cultivated appearance scarcely warranted by the exterior. In Winter, the sod-dwellings are easily warmed and but little affected through the thick non-conducting walls by the furious gales which sweep down from the north-west, bringing snow and ice and wintery desolation; while in Summer, they are, with proper ventilation, probably the coolest and most healthful habitation that could be devised.

Frequently, in order to save time in the construction, a location is chosen on an abrupt hill-side, and an excavation made which, with the wall built up around it, forms the house on the same plan that "side-hill basements," with stone walls and "cellar-kitchens" are constructed. This, while securing ease in construction, precludes proper ventilation and light, and is usually only resorted to temporarily by those with whom time or assistance are lacking, and, after a year or more of useful existence, these "dugouts," as they are termed, give way to the more pretentious and comfortable "doby."

As for the dwellers in these curious homes, the devotees of " doby," they are in all respects the same as humanity elsewhere. The farmer, and they are mostly farmers, rises at early dawn and labors throughout the day at the plow or in the harvest-field, and at night, with a prayer for divine protection and guidance, seeks that rest which honest toil affords. The children grow up strong and vigorous on the homely, healthful fare; they obtain the rudiments of an education in the doby school-house, and learn the story of the cross at the Sabbath-school and Church. During the Summer season, they wander over the prairies gathering flowers or hunting the eggs of the prairie-chicken, and in Winter, with the parents, after the crops are secured and the Autumn's tasks completed, they gather at the fireside of evenings, and, while the corn, the principal fuel in this prairie region, crackles and burns brightly in the fire, they peruse the weekly paper published at the county town, discuss neighborhood gossip, feast upon pop-corn and molasses-candy, or join in singing familiar hymns from their Sunday-school tune books or Church melodies. Spelling - bees, singing - schools, Grange and Good Templar " lodges" are as numerous with them as in the sections further east, and there are the same society heart-burnings, the same striving after dress and dignity, and the same marrying and giving in marriage that characterize society every-where, whether in dwellings of sod or brick or marble.

To the West the sod-house has been the means of unparalleled development and usefulness; to those who have adopted it, it has been a means of wealth and contentment, for a home and a means of support are both. To the treeless but fertile prairies it has brought settlers innumerable, who could not have come but for it; to the settlers it has given homes and the means of making their own the lands which may be had by a residence and cultivation. Many there are who,

had they been obliged to purchase building material and transport it hundreds of miles by wagon, must have waited many a weary year, but who, through the aid of "doby," not only made themselves a shelter and a home, but secured for themselves the fertile acres which may be had for the taking in this asylum for the persecuted, poverty-stricken sons of men every-where.

All over the western country, from the Missouri River to the Rocky Mountains, and from Dakota to the Rio Grande, doby reigns supreme. Not that all the residences are thus built, for there are in places many wooden dwellings; and in the towns and along the railroads and rivers, houses of wood, and sometimes of brick and stone, have taken the place of the less pretentious sod-dwellings; but in the newly settled regions, the sections which God's poor seek out in which to struggle with fortune and build houses for the families he has given them, doby is the priceless treasure, the boon which enables them to obtain a foothold, the free gift of nature, which furnishes shelter, and the medium through which come the blessings of home and happiness, and a trust in God and his overshadowing providence.

THE gold fever of 1859-60, and the consequent rush across the Plains, established a line of sod-houses from the Missouri River to the Rocky Mountains, which have developed one of the most important sections of our country, and opened the door of thousands of comfortable and substantial homes to the honest homesteaders of the West. Fifteen years ago, the belt of country lying between the Rocky Mountains, on the west, and the Missouri River, on the east, and stretching indefinitely north and south, was considered as a worthless waste, a treeless, uninhabitable section, without soil, building material, water, or protection against the biting, blinding storms of Winter, which swept furiously down from the mountain fastnessess of the great unexplored, uninvaded home of the storm king of North America. Today the sod-house, the advance-guard of civilization and enterprise in the extreme West, has developed the agricultural adaptability of the Western Desert, invaded and made public the secret domain of the vEolus of our continent, furnished homes and fortunes to hundreds of thousands of God's children, and developed, by its own peculiar adaptability, the resources and wealth of an important section of our country, the great grain and stock producing region of the Missouri Valley. What the log-hut was to the early settlers of New England, the sod

house, "doby," or "dug-out," has been to the pioneer on the prairies of the Missouri Valley. The same force of circumstances which gave the log-house an important position in the history of the eastern half of our great country, has made the sod dwelling an equally important factor in the development of the western portion, and entitled it to a place beside its earlier, but scarcely less substantial or respectable, brother at the Centennial Exposition, and in the history of the great country of countries, the home of the honest toiler, of whatever race or condition.

Strange as it may appear to those unacquainted with the fact, there are tens, perhaps hundreds, of thousands of people in the Missouri Valley, living to-day in houses of sod, turf taken from God's green sward of the great West, laid up with mortar which nature kindly furnishes prepared, and plastered inside with the sandy loam which underlies the black alluvium from which the varied vegetation springs. Within these homes, comfortable beyond the log or frame house of the timbered regions, and equally cleanly and healthful, families are reared, the elements of education dispensed, seeds of piety sown, and the foundation of future fame and fortune successfully laid. Beneath their fostering influence the great fertile but treeless plains have been brought under cultivation, the elements have been made subject to the wants of mankind, towns have sprung up in the uninhabited waste, the iron horse has been called to his duty in their domain, the great agricultural wealth of the country developed, and the desert made to blossom as the rose. To the sod-house of the West belongs honors innumerable, belongs the credit of the thrift and prosperity with which the Missouri Valley is to-day graced and made happy.

It was my fortune, in 1859, to visit the then uninhabited and almost unknown section west of the Missouri, and to witness the construction and practical test of the then novelty, a dwelling composed of turf from the surrounding prairies. It has been my fortune since to watch, with a considerable degree of interest, the development of this to be great grain and stock belt of the Union, and to note, with the care which its novelty and peculiarities suggested, the influence which this great factor, the sod-house, has had in determining the growth and importance of the country. The cry of gold in the Pike's Peak region drew, at the date mentioned, large numbers of people thither, to supply whom with food became the business of the settlers then scattered along the Missouri River, within a few miles of its waters, and in reach of the scanty forests with which its banks are fringed. All provisions, clothing, and mining accouterments were freighted across this then uninhabited section, nearly a thousand miles in width, by teams of horses and cattle. Along the roads which these freighters had laid out, and which all the travel followed, enterprising "ranchemen," bent upon securing a portion of the profits of the season, established themselves for the sale of needed articles to the freighters, whose trips then occupied months instead of, as now, days, and for furnishing meals to the passengers on the stage-coaches, a line of which had been early established. The tents and temporary shelters, which these caterers had provided themselves, soon becoming insufficient, they cast

about for some more commodious and substantial shelters for themselves and guests, the numbers of which were rapidly increasing. In the earlier days of military rule in that region, many of the buildings at Forts Kearney, Leavenworth, and other military posts, had, for want of timber, been constructed of adobe, or sun-dried bricks, the art of making which had been learned from the Mexicans, with whom the military on the western plains had been brought in contact. These were used in some instances by the ranchemen, until the idea of using sods instead suggested itself to the inventive genius of the necessitated housebuilder, and the sod-house became a success. The method, source, and result of the two were so nearly related that the name of adobe, or "doby," as it was every-where known, which properly belonged to the sun-dried bricks, was also given the sod; and henceforth the sod, or "doby," house became an important element of life in the Missouri Valley.

Constant association or familiarity with "doby" failed, in this instance, to breed contempt; and the Missouri Valley settler, who, in freighting his farm products across the plains (and nearly everyone did so), became more thoroughly acquainted with and accustomed to the sod-house, came to recognize its value, and to look upon it as a valuable aid in the economy of prairie life. Those who had substantial wooden homes on the Missouri so far recognized the practical value of "doby" as to make immediate use of the principle on their farms, in the construction of sod out-houses, and various buildings which they might chance to need; and thus the sod-house took another step in advance, and demonstrated its practical utility and durability beside its more pretentious wooden prototype. From this point the transition was easy. The son, who had grown up familiar with the "doby," and been thoroughly convinced of its use and durability, becoming of age, and desirous of erecting a claim shanty on government land, and making a homestead his own by a temporary residence a few days of each year thereon, readily adopted the sod-house as a visible habitation, the material for which was convenient, and the practicabihty thoroughly tested. Later, when the want for a permanent home came about, with the fashion already inaugurated, and the practicability and cheapness especially apparent, there was little difficulty in the adoption of doby as the material for a dwelling, and the home to which the willing, true - hearted, devoted bride was borne. Of the hundreds of thousands of young couples who have made their homes on the prairies of the Missouri Valley, probably more than half owe their first home together, and much of their success, to doby.

The method of construction is not unlike that of the brick dwelling, except that mortar is not always used in laying the sods. A "breaking" plow, such as is used in subduing prairie-grass, and preparing the soil for cultivation, turns the sod in strips, perhaps a foot in width, and of indefinite length. They are then cut in pieces about two and a half feet long, by means of a spade, and are ready for the wall. They are laid up with as much care and nicety as the native skill of the builder can produce, and the edges carefully trimmed with a sharp spade, so that the wall, when completed, is as smooth, and, after being thoroughly dried, is also equally as solid as a brick wall. Window and door frames are set in as in the construction of brick buildings, and the houses are covered sometimes with shingles, sometimes with a thatch of the long prairie grass from the low grounds, and sometimes with several layers of sod cut to turn the rain and make tight joints. Frequently they are divided into several rooms by walls of sod, and occasionally they are two or more stones in height; but usually they are built but one story in height, and with only one room, which is subdivided by light wooden partitions, or in some cases by blankets. The walls, when completed, are plastered smoothly inside, and, being thoroughly whitewashed, present a neat and eminently

healthful and cleanly appearance. The "best room" is papered and carpeted, the walls adorned with pictures, while the vines trained about the door and windows lend their cheerful and refining influence, and the whole, when once inside and the idea of "sod-house" forgotten, has a homelike and cultivated appearance scarcely warranted by the exterior. In Winter, the sod-dwellings are easily warmed and but little affected through the thick non-conducting walls by the furious gales which sweep down from the north-west, bringing snow and ice and wintery desolation; while in Summer, they are, with proper ventilation, probably the coolest and most healthful habitation that could be devised.

Frequently, in order to save time in the construction, a location is chosen on an abrupt hill-side, and an excavation made which, with the wall built up around it, forms the house on the same plan that "side-hill basements," with stone walls and "cellar-kitchens" are constructed. This, while securing ease in construction, precludes proper ventilation and light, and is usually only resorted to temporarily by those with whom time or assistance are lacking, and, after a year or more of useful existence, these "dugouts," as they are termed, give way to the more pretentious and comfortable "doby."

As for the dwellers in these curious homes, the devotees of " doby," they are in all respects the same as humanity elsewhere. The farmer, and they are mostly farmers, rises at early dawn and labors throughout the day at the plow or in the harvest-field, and at night, with a prayer for divine protection and guidance, seeks that rest which honest toil affords. The children grow up strong and vigorous on the homely, healthful fare; they obtain the rudiments of an education in the doby school-house, and learn the story of the cross at the Sabbath-school and Church. During the Summer season, they wander over the prairies gathering flowers or hunting the eggs of the prairie-chicken, and in Winter, with the parents, after the crops are secured and the Autumn's tasks completed, they gather at the fireside of evenings, and, while the corn, the principal fuel in this prairie region, crackles and burns brightly in the fire, they peruse the weekly paper published at the county town, discuss neighborhood gossip, feast upon pop-corn and molasses-candy, or join in singing familiar hymns from their Sunday-school tune books or Church melodies. Spelling - bees, singing - schools, Grange and Good Templar " lodges" are as numerous with them as in the sections further east, and there are the same society heart-burnings, the same striving after dress and dignity, and the same marrying and giving in marriage that characterize society every-where, whether in dwellings of sod or brick or marble.

To the West the sod-house has been the means of unparalleled development and usefulness; to those who have adopted it, it has been a means of wealth and contentment, for a home and a means of support are both. To the treeless but fertile prairies it has brought settlers innumerable, who could not have come but for it; to the settlers it has given homes and the means of making their own the lands which may be had by a residence and cultivation. Many there are who,

had they been obliged to purchase building material and transport it hundreds of miles by wagon, must have waited many a weary year, but who, through the aid of "doby," not only made themselves a shelter and a home, but secured for themselves the fertile acres which may be had for the taking in this asylum for the persecuted, poverty-stricken sons of men every-where.

All over the western country, from the Missouri River to the Rocky Mountains, and from Dakota to the Rio Grande, doby reigns supreme. Not that all the residences are thus built, for there are in places many wooden dwellings; and in the towns and along the railroads and rivers, houses of wood, and sometimes of brick and stone, have taken the place of the less pretentious sod-dwellings; but in the newly settled regions, the sections which God's poor seek out in which to struggle with fortune and build houses for the families he has given them, doby is the priceless treasure, the boon which enables them to obtain a foothold, the free gift of nature, which furnishes shelter, and the medium through which come the blessings of home and happiness, and a trust in God and his overshadowing providence.

Wednesday, February 18, 2015

1851 Fashions

I'm limited in what I could find from 1851 but here are the five images I've found so far and these are French fashions.

Tuesday, February 17, 2015

Hammers

Hammers haven't changed too much since the 19th Century however this excerpt from Knight's American Mechanical Dictionary ©1881 gives some great insights in which hammer to use for each job, as well as some historical information.

Ham'mer. 1. A tool for driving nails, beating metals, and the like.

We can hardly admit the statement of riiny that the hammer was invented by Cinyra, the discoverer of copper-mines in the island of Cyprus. Tools of metal, of which the hammer was among the first, must have been in use for many centuries. Tubal Cain, the descendant in the sixth generation from Cain, was an "artificer in brass and iron" ; copper, probably, rather than brass. Brass and bronze are not distinguished from each other, by name, cither in Greek or Latin.

The initial form was perhaps a stone fastened to a handle, and used as a club, A, B, C, D, E. Many such are found in the relics of the stone age, before man had learned the use of metal, the most useful of which, iron, was about the last to be discovered, of those which are applied to the common affaire of life. This stone age is so far in the remote past as to antedate all historical accounts of manners, customs, and appliances. The use of stone, however, in the mode described, still exists among many nations imperfectly provided with a better substitute. In the Bible we read of hammers for nails, forging, and planishing, and for breaking stone.

A B are ancient stone hammers, found in longneglected workings of the Lake Superior copper region, and are identical with those of other parts of the world. It is not necessary to give them an equal antiquity to the "celts," stone axes and hammers of the stone age of Europe, as many of the implements yet in use among the more barbarous North American Indians are of the same general character. See AXK.

Modern hammers are of many shapes and kinds. The parts are the Jiaiullc and head. The latter lias an eye, fact, peen, or claw.

F shows a riveting hammer. Of its parts a is the face, b the poll, c the eye, d the peen, e the helve.

G is a large hammer used by machinists. Between F and G is a claW, which takes the place of the peen of the other hammer. I and J are miners' hammers; K a miner's wedge.

Haininer-making forms a very important part of the industry of the great manufacturing center, Birmingham, and its satellite, Wolverhampton.

The nomenclature of the various kind*, which are numerous, is generally derived from their application, though iu some instances from the form.

File-maker's, sledge, riveting, lift, raising, claw, planishing, gold-beater's, hacking, veneering, may be enumerated among the numerous varieties, as well as tilt and steam hammers.

Hammers employed in engine work are of three sizes, the sledge, flogging, and hand hammers. See

also Miner's Hammer.

Ham'mer. 1. A tool for driving nails, beating metals, and the like.

We can hardly admit the statement of riiny that the hammer was invented by Cinyra, the discoverer of copper-mines in the island of Cyprus. Tools of metal, of which the hammer was among the first, must have been in use for many centuries. Tubal Cain, the descendant in the sixth generation from Cain, was an "artificer in brass and iron" ; copper, probably, rather than brass. Brass and bronze are not distinguished from each other, by name, cither in Greek or Latin.

The initial form was perhaps a stone fastened to a handle, and used as a club, A, B, C, D, E. Many such are found in the relics of the stone age, before man had learned the use of metal, the most useful of which, iron, was about the last to be discovered, of those which are applied to the common affaire of life. This stone age is so far in the remote past as to antedate all historical accounts of manners, customs, and appliances. The use of stone, however, in the mode described, still exists among many nations imperfectly provided with a better substitute. In the Bible we read of hammers for nails, forging, and planishing, and for breaking stone.

A B are ancient stone hammers, found in longneglected workings of the Lake Superior copper region, and are identical with those of other parts of the world. It is not necessary to give them an equal antiquity to the "celts," stone axes and hammers of the stone age of Europe, as many of the implements yet in use among the more barbarous North American Indians are of the same general character. See AXK.

Modern hammers are of many shapes and kinds. The parts are the Jiaiullc and head. The latter lias an eye, fact, peen, or claw.

F shows a riveting hammer. Of its parts a is the face, b the poll, c the eye, d the peen, e the helve.

G is a large hammer used by machinists. Between F and G is a claW, which takes the place of the peen of the other hammer. I and J are miners' hammers; K a miner's wedge.

Haininer-making forms a very important part of the industry of the great manufacturing center, Birmingham, and its satellite, Wolverhampton.

The nomenclature of the various kind*, which are numerous, is generally derived from their application, though iu some instances from the form.

File-maker's, sledge, riveting, lift, raising, claw, planishing, gold-beater's, hacking, veneering, may be enumerated among the numerous varieties, as well as tilt and steam hammers.

Hammers employed in engine work are of three sizes, the sledge, flogging, and hand hammers. See

also Miner's Hammer.

Monday, February 16, 2015

Caring for Boot & Shoe Leather

Below is some helpful information and instructions for taking care of boot and shoe leather. These tidbits come from The Art of Boot and Shoemaking ©1885

USEFUL RECEIPTS FOR SHOEMAKERS

Varnish for Shoes.—Put half a pound of gum shellac broken up into small pieces in a quart bottle or jug, cover it with alcohol, cork it tight, and put it on a shelf in a warm place; shake it well several times a day, then add a piece of camphor as large as a hen's egg; shake it again and add one ounce of lamp-black. If the alcohol is good it will be all dissolved in three days; then shake and use. If it gets too thick, add alcohol; pour out two or three tea-spoonfuls in a saucer, and apply it with a small paintbrush. If the materials are all good, it will dry in about five minutes, and will be removed only by wearing it off, giving a gloss almost equal to patent leather. The advantage of this preparation over others is, it does not strike into the leather and make it hard, but remains on the surface, and yet excludes the water almost perfectly. This same preparation is admirable for harness, and does not soil when touched as lamp-black preparations do.

Jet for Boots or Harness.—Three sticks of the best black sealing-wax, dissolved in half a pint of spirits of wine, to be kept in a glass bottle, and well shaken previous to use. Apply it with a soft sponge.

Castor-oil as a Dressing for Leather.—Castor-oil, besides being an excellent dressing for leather, renders it vermin proof. It should be mixed, say half and half, with tallow and other oil. Neither rats, roaches, nor other vermin will attack leather so prepared.

Composition for Leather.—Take one hundred parts of finely pulverised lamp-black, and thirty parts of East India copal, previously dissolved in rectified turpentine. Mix the two together until the whole forms a homogeneous paste. To this is to be added fifteen parts of wax and one part of india-rubber, which has been first dissolved in some ethereal oil. When the whole is properly mixed, a current of oxygen is passed for half an hour through the mass, and after cooling, the whole is to be thoroughly worked up. It may then be packed in tin boxes, and kept ready for use.

Waterproofing.—Half a pound of shoemaker's dubbin, half a pint of linseed oil, and half a pint of solution of india-rubber. Dissolve with a gentle heat and apply. Note these ingredients are inflammable, and great caution must be used in making the preparation.

To Bender Cloth Waterproof.—The following is said to be the method used in China. To one ounce of white wax melted, add one quart of spirits of turpentine, and when thoroughly mixed and cold, dip the cloth into the liquid, and hang it up to drain and dry. Muslins, as well as strong cloths, are by this means rendered impenetrable to rain, without losing their colour or beauty.

To preserve Boots from being penetrated by Wet and Snow Damp.—Boots and shoes may be preserved from wet by rubbing them over with linseed oil, which has stood some months in a leaden vessel till thick. As a securityagainst snow water, melt equal quantities of beeswax and mutton suet in a pipkin over a slow fire. Lay the mixture, while hot, on the boots and shoes, and rub dry with a woollen cloth.

Waterproofing Compositions for Leather.—Melt over a slow fire one quart of boiled linseed oil, a pound of mutton suet, three quarters of a pound of yellow beeswax, and half a pound of common resin. With this mixture rub over the boots or shoes, soles, legs, and upper leathers, when a little warmed, till the whole are completely saturated. Another way is, to melt one quart of drying oil, a quarter of a pound of drying beeswax, the same quantity of spirits of turpentine, and an ounce of Burgundy pitch. Hub this composition, near a fire, all over the leather, till it is thoroughly saturated.

Chinese Waterproofing Composition for Leather.— Three parts of blood deprived of its fibrine, four of lime, and a little alum.

Polishing up Old and Soiled Boots.—If required to tell in the fewest words how to dispose of old goods, we should say, make them as much like new as possible. We would then go further, and advise never to let them get old. This may be thought rather difficult, but still it can be put in practice so far as to make it a piece of first-rate counsel. Some may think it a good plan to put the lowest possible price on them, and keep them in sight as a temptation to buyers, without taking any other trouble. But if this is a very easy effort, we think ours is far more profitable to the seller, and therefore worthy of being explained somewhat minutely. Among the things that ought to be in every shoe shop, besides the necessary tools, are blacking, gum tragacanth, gum arabic, varnish, neatsfoot oil, and perhaps some prepared dressing for uppers. With these, or such of them as may be necessary, on old upper, however rusty looking, if properly treated, can be made to shine. Ladies' shoes, if of black morocco ar kid, and have become dry, stiff, and dull, try a little oil on them—not a great deal—which will make them more soft and flexible, and will not injure the lustre materially. Then try a delicate coating of prepared varnish, designed for the purpose, over the oil. When this has dried the shoes will doubtless be improved. If a calf kid begins to look reddish and rusty, give it a slight application of oil, which will probably restore the colour; but, if not, put on blacking. When the blacking is dry, brush it off, and go over it again very lightly with the oil, when it will be as good as new. Patent leather will not only be made softer, but the lustre will also be improved, by oiling. For pebbled calf, or any kind of grain leather that has become brown, the treatment should be the same; when only a little red, an application of oil, or even tallow, will often restore the colour. When it is very brown, black it thoroughly, and oil it afterwards, giving it a nice dressing of dissolved gum tragacanth to finish. This is the grand recipe for improving uppers; the labour of applying it is very little, and the effect very decided and gratifying. For men's boots that have been much handled, often tried on, or have become rough, or dry, stiff and lifeless, from lying in shop a long time, or all these things together, another treeing is the best thing in the world, and precisely what they need. It should be done thoroughly. After putting them on the trees, a supply of oil must not be forgotten. Then a dressing of gum tragacanth, and, when it is partially dry, a rubbing with a long-stick to give a polish, after which a second and slight application of gum, to be rubbed off with the bare hand before fully dry. It is almost surprising how much a boot is renewed by this treatment, and, though it may require half an hour's time to each pair from some man who understands it, the cost is well expended and many times returned. A good supply of trees, of different sizes, should be always at hand, and not be allowed to get dusty for want of use. But when, for any reason, it is inexpedient or difficult to apply a thorough process with old boots, they can still be oiled and gummed without using the trees, and though with less good effect, yet still enough to prove very useful.

If any mould has shown, or the grease used in stuffing has drawn out of the leather, a little rubbing off with benzine would be necessary at first to clean them. After this an application of cod oil and tallow might be useful to make the leather soft and pliable; to be preceded, if the colour is a little off, by an application of a prepared black of some kind, of which there are several in the market. The soles would probably be improved by cleaning and a vigorous use of the rub-stick; they might also be rebuffed, if the stock would stand it, and a slight application of size would help to give them a polish. To do all this well requires some skill, and the expenditure of considerable labour.

To Restore the Blackness of Old Leather.—For every two yolks of new-laid eggs, retain the white of one; let these be well beaten, and then shaken in a glass vessel till as thick as oil. Dissolve in about a table-spoonful of Holland gin, a piece of lump sugar, thicken it with ivory black, and mix the eggs for use. Lay this on in the same manner as blacking for shoes, and after polishing with a soft brush, let it remain to harden and dry. This process answers well for ladies' and gentlemen's leather shoes, but should have the following addition to protect the stockings from being soiled: Shake the white or glaire of eggs in a phial till it is like oil, and lay some of it on twice with a small brush over the inner edges of the shoes.

To Clean Boot Tops.—Dissolve an ounce of oxalic acid into a pint of soft water, and keep it in a bottle well corked; dip a sponge in this to clean the tops with, and if any obstinate stains remain rub them with some bath brick dust, and sponge them with clean water. If your tops are brown, take a pint of skimmed milk, half an ounce of spirits of salts, as much of spirits of lavender, one ounce of gum arabic, and the juice of two lemons. Put the mixture into a bottle closely corked; rub the tops with a sponge, and when dry, polish them with a brush and flannel.

To Polish Enamelled Leather.—Two pints of the best cream, one pint of linseed oil; make them each lukewarm, and then mix them well together. Having previously cleaned the shoe, &c, from dirt, rub it over with a sponge dipped in the mixture; then rub it with a soft dry cloth until a brilliant polish is produced.

Softening Boot Uppers.—Wash them quite clean from dirt and old blacking, using lukewarm water in the operation. As soon as clean and the water has soaked in, give them a good coating of currier's dubbin, and hang them up to dry; the dubbin will amalgamate with the leather, causing it to remain soft and resist moisture. No greater error could possibly be committed than to hold boots to the fire after the application of, or when applying oil or grease. All artificial heat is injurious. Moreover, it forces the fatty substance through and produces hardness, instead of allowing it to remain and amalgamate with the leather. Note this opinion about heat, and act as experience dictates. "We think, if the heat be not too great, no harm will result.

Cleaning Buckskin Gloves and White Belts.—Should these be stained, a solution of oxalic acid must be applied; should they be greasy, they must be rubbed with benzine very freely. After these processes are complete some fine pipeclay is to be softened in warm water to the consistency of cream; if a good quantity of starch be added to this it will prevent this white clay from rubbing off, but the whiteness will not then be so bright. If a small quantity be used the belts will look very bright. This mixture is to be applied with some folds of flannel as evenly as possible, and put to dry in the sun or in a warm room. When dry, the gloves can be put on and clapped together; this will throw off a good deal of superfluous pipeclay. The belts are to be treated in a similar way.

To take Stains out of Black Cloth, &c Boil a quantity

of fig-leaves in two quarts of water, till reduced to a pint. Squeeze the leaves, and bottle the liquor for use. The articles, whether cloth, silk, or crape, need only be rubbed over with a sponge dipped in the liquor.

Liquid for Cleaning Cloth.—Dissolve in a pint of spring water one ounce of pearlash, and add thereto a lemon cut in slices. Let the mixture stand two days, and then strain the clear liquor into bottles. A little of this dropped on spots of grease will soon remove them, but the cloth must be washed immediately after with cold water.— Or, put a quart of soft water, with about four ounces of burnt lees of wine, two scruples of camphor, and an ox's gall, into a pipkin, and let it simmer till reduced to one half, then strain, and use it while lukewarm. Wet the cloth on both sides where the spots are, and then wash them with cold water.

How to Remove Ink Stains.—Owing to the black colour of writing ink depending upon the iron it contains, the usual method is to supply some diluted acid in which the iron is soluble, and this, dissolving the iron, takes away the colour of the stain. Almost any acid will answer for this purpose, but it is, of course, necessary to employ those only that are not likely to injure the articles to which they are applied. A solution of oxalic acid may be used for this purpose, and answers very well. It has, however, the great disadvantage of being very poisonous, which necessitates great caution in its use. Citric acid and tartaric acid, which are quite harmless, are therefore to be preferred, especially as they may be used on the most delicate fabrics without any danger of injuring them. They may also be employed to remove marks of ink from books, as they do not injure printing ink, into the composition of which iron does not enter. Lemon juice, which contains citric acid, may also be used for the same purpose, but it does not succeed so well as the pure acid.

Kid or Memel Colour Renovator. — Take a few cuttings of loose kid, pour over sufficient water to just cover them, and simmer them for an hour. When cool they will be of the proper consistency. Apply with the fingers or a piece of rag or cloth.

French Polish for Boots Mix together two pints of

best vinegar, one pint of soft water, and stir into it a quarter pound of glue broken up, half a pound of logwood chips, a quarter of an ounce of best soft soap, and a quarter of an ounce of isinglass. Put the mixture over the fire and let it boil for ten minutes or more, then strain the liquid and bottle and cork it. When cold it is fit for use. It should be applied with a clean sponge. Fluid for Renovating the Surface of Japanned Leather.

—This liquid, for which Mr. "William Hoey obtained provisional protection in 1863, was described as being applicable for boots, shoes, and harness. It was composed , of about 2 ounces of paraffin or rock oil, or a mixture of both in any proportion, \ drachm of oil of lavender, \ drachm of citrionel essence, and 5 an ounce of spirit of ammonia; sometimes ivory or lamp-black was added to colour the mixture. When the ingredients were thoroughly mixed together, the fluid was applied lightly on the surface of the leather or cloth.

To Separate Patent Leather Patent leather is an

article with which there is always more or less liability to trouble in handling and working. It is sensitive to very warm weather, and great care is needed during the cold season.

If it should stick, and cold be the cause of the sticking, lay out the skin on a wide board, and with a hot flat-iron give it a rather slow but thorough ironing around the edges, where most of the trouble exists. A couple of thicknesses of cotton cloth are necessary to keep the iron from touching the leather. When both parts are well warmed through there will probably be no difficulty about their separation.

When the difficulty is owing to hot weather, the skins should be put away in the cellar, or the coolest place within reach and left till cooled through, when unless the stick is a very strong one, they will offer little resistance to being pulled apart.

If the stick be a slight one, open it gently and breathe on it as you pull.

To Preserve Leather from Mould.—Pyroligneous acid may be used with success in preserving leather from the attacks of mould, and is serviceable in recovering it after it has received that species of damage, by passing it over the surface of the hide or skin, first taking due care to remove the mouldy spots by the application of a dry cloth.

USEFUL RECEIPTS FOR SHOEMAKERS

Varnish for Shoes.—Put half a pound of gum shellac broken up into small pieces in a quart bottle or jug, cover it with alcohol, cork it tight, and put it on a shelf in a warm place; shake it well several times a day, then add a piece of camphor as large as a hen's egg; shake it again and add one ounce of lamp-black. If the alcohol is good it will be all dissolved in three days; then shake and use. If it gets too thick, add alcohol; pour out two or three tea-spoonfuls in a saucer, and apply it with a small paintbrush. If the materials are all good, it will dry in about five minutes, and will be removed only by wearing it off, giving a gloss almost equal to patent leather. The advantage of this preparation over others is, it does not strike into the leather and make it hard, but remains on the surface, and yet excludes the water almost perfectly. This same preparation is admirable for harness, and does not soil when touched as lamp-black preparations do.

Jet for Boots or Harness.—Three sticks of the best black sealing-wax, dissolved in half a pint of spirits of wine, to be kept in a glass bottle, and well shaken previous to use. Apply it with a soft sponge.

Castor-oil as a Dressing for Leather.—Castor-oil, besides being an excellent dressing for leather, renders it vermin proof. It should be mixed, say half and half, with tallow and other oil. Neither rats, roaches, nor other vermin will attack leather so prepared.